စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

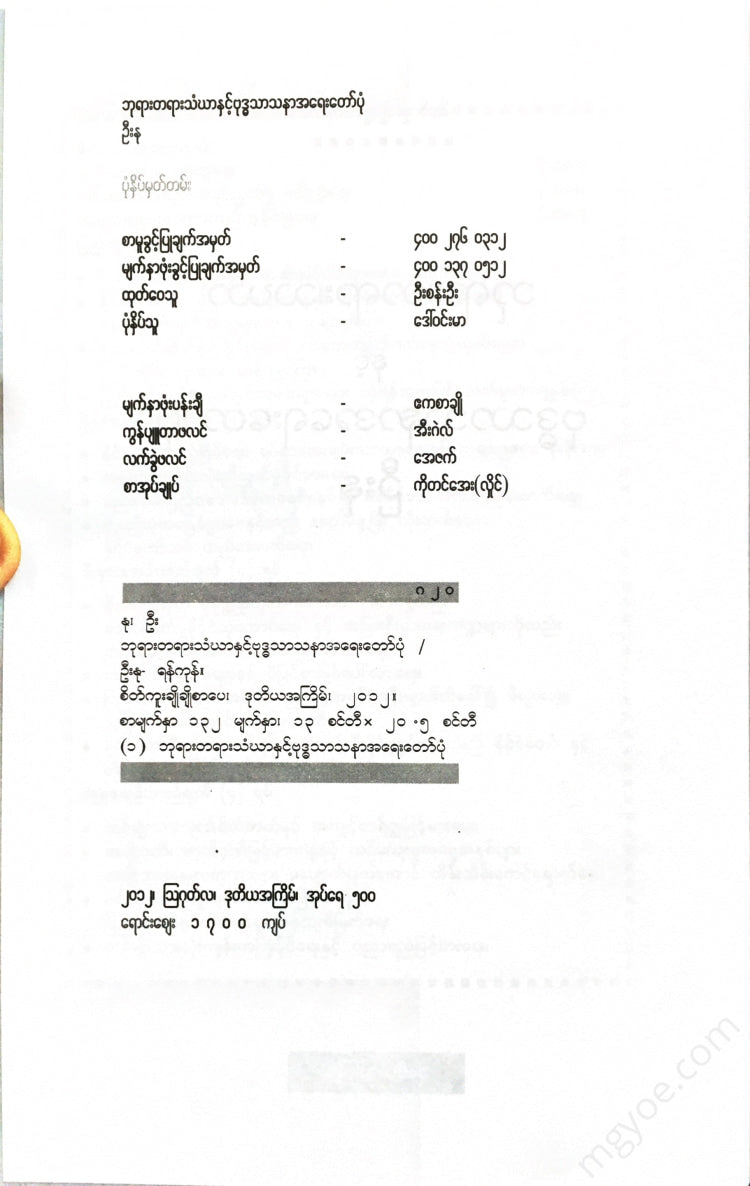

U Nu - The Story of the Buddhist Monks and the Buddhist Rebellion

U Nu - The Story of the Buddhist Monks and the Buddhist Rebellion

Couldn't load pickup availability

About the Buddha

Prime Minister U Nu's speech

Distinguished guests and distinguished guests,

Today I want to talk about God. When talking about God, I think it would be necessary to briefly explain the background first so that the audience can understand it more easily.

In addition to the humans and animals that we can see with our eyes, there are many other creatures in the world. If we were to describe the creatures in the world by type, they would be:

(1) Brahmas, (2) Devas, (3) Humans, (4) Animals, (5) Demons, (6) Asuras,

(7) They are the children of hell.

These beings become various beings, and when the time comes, they die. After death, they do not disappear. Brahmas die and become devas. They become humans. When they die as devas, they become animals, demons, asuras, hells, and hellling beings. Similarly, when devas, humans, animals, demons, asuras, hells, and hellling beings die, according to the merits and demerits they have done, as I have just said, they become one of the following: Brahmas, devas, humans, animals, demons, asuras, hellling beings, hellling beings. They cannot but become again.

Such Brahmas, devas, humans, animals, demons, asuras, hell dwellers, and hell children, repeatedly growing old, getting sick, and dying, are all extremely terrible sufferings.

Only when a Buddha appears can beings hear the Dhamma that can free them from these sufferings and strive to do so, and so many Brahmas, devas, and humans are freed from the sufferings of aging, illness, and death, never to be reborn again after death. This Dhamma also disappeared a long time after the Buddha entered Nibbana. It will only reappear when another Buddha appears.

That is why good people make the intention to become Buddhas with the intention of saving these beings from suffering. Just making that intention does not make one a Buddha. It takes many lifetimes of effort to make this intention a Buddha. For example, a person who wants to save people who are suffering from diseases would first make the intention to become a doctor. Just making that intention does not make one a doctor. To become a doctor, one would have to spend many years practicing medicine.

There are ten major tasks that people who pray to become Buddhas must perform. These major tasks are called parami in Pali. Parami is the task that is required to become Buddhas. These major tasks are:

(1) The virtue of giving generously, starting with one's property, children, and wife, and ending with one's life.

(2) The virtue of taking special care of one's body and mouth so as not to commit or utter wrongdoing.

(3) Before attaining the nirvana of renunciation of sensual pleasures.

(4) The wisdom of acquiring knowledge that can bring happiness to beings and making them happy.

(5) The virtue of striving extremely hard for the welfare of sentient beings.

(6) The virtue of patience, which is special patience in every place.

(7) The virtue of loyalty, which means keeping promises made, regardless of life or death.

(8) It means to do something without considering the risk of death when you have decided to do something.

(9) The virtue of loving-kindness, which is to have a loving mind towards all beings, regardless of their inferiority, middle class, or superior status.

(10) The ten virtues of equanimity are self-control, both when one's desires are fulfilled and when they are not fulfilled, so that one's mind is neither excited nor depressed.

These ten great works are divided into three categories: low, medium, and high. It is not easy to achieve 100% success in all three. It cannot be achieved in one lifetime. It cannot be achieved in a hundred or a thousand lifetimes. Only through countless lifetimes of effort can one achieve 100% success in these ten great works.

To make the ten perfections easier to understand, I would like to tell you an incident from the life of the Bodhisattva Monkey King. A brahmin named Devadatta was searching for a lost cow when he lost his way in the forest and fell into a ravine. The Bodhisattva Monkey King saw the brahmin falling into the ravine.

(1) As soon as he saw the Brahmin in such distress, a feeling of compassion and love arose in the mind of the Bodhisattva Monkey King, as if he were seeing his own son in a pit of despair, and he wanted him to be happy.

(2) So the Bodhisattva Monkey King promised to save the Brahmin's life at the risk of his own. He did as he promised. I will tell you how he did it.

(3) After the Bodhisattva Monkey King made a promise to the Brahmin, he began to think about how he could rescue him from the cliff. When he thought about it, he came up with the idea that the only way to do it was to carry the Brahmin and jump over the cliff.

(4) However, if the Brahmin fell down without reaching the top, he would die. So, just to try it out, he picked up a large stone that was about the same weight as the Brahmin and jumped up and down several times. After trying this, he was confident that he could carry the Brahmin and jump up to the top.

(5) In saving this Brahmin, the Bodhisattva Monkey King knew that he could die, but he sacrificed his own life to save the Brahmin's life.

(6) After saving the Brahmin, the Bodhisattva Monkey King was very tired and slept on the Brahmin's lap for a while. At that time, the Brahmin, intending to take the monkey meat home to eat, hit the Monkey King on the head with a stone. The Monkey King suffered a serious head injury and ran up a tree. The Brahmin hit his head with a stone in this way, causing him great pain, but he did not get angry with the Brahmin and tolerated it.

(7) And he does not physically harm a Brahmin, nor does he verbally abuse him.

(8) The Buddha, the Monkey King, ignored the Brahmin's attempt to commit suicide.

(9) Not only that, the Bodhisattva Monkey King jumped from tree to tree, looking for a way out of the Brahmin forest with the blood dripping from his head wound. True to his resolve to save him to the end, the Bodhisattva Monkey King saved him.

(10) The Buddha did not save the Brahmin out of any desire for gain. He did so by sacrificing his own interests and suffering.

In that novel-

(1) The monkey king, Alaungdaw, risked his life to save the Brahmin, which was a great act of charity.

(2) Even if a Brahmin hits his head with a stone, he does not physically harm the Brahmin or verbally abuse him, but he guards his body and speech. This is a virtue.

(3) Not expecting any benefit for oneself when rescuing a Brahmin is a sin.

(4) It is wise to explore ways to free the Brahmin from the abyss.

(5) The effort of repeatedly jumping over a stone of equal weight to a Brahmin is a sign of perseverance.

(6) It is the virtue of fortitude to control one's mind so as not to become angry with a brahmin, even when one experiences severe pain, almost breaking one's bones, because one's head is hit with a stone.

(7) Having promised to save the life of a Brahmin, not breaking this promise, regardless of one's own life, is the virtue of loyalty.

(8) Having decided to save the Brahmin to the end, the Brahmin plans his own death, but carries out his original decision to the end without fail is the meaning of the word.

(9) When the monkey king Alaungdaw saw the brahmin falling into the abyss, he thought of his own son falling into the abyss.