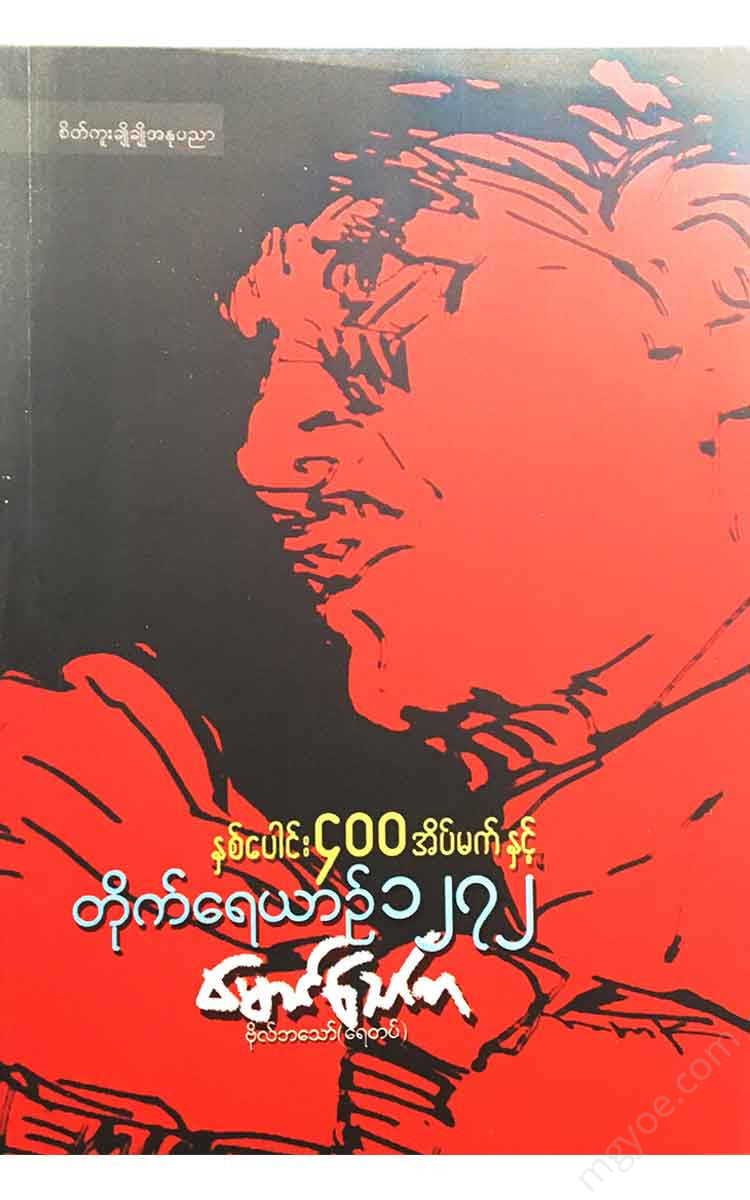

စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

Maung Thaw Ka - 400 Years of Dreams and the Battle of Tai Yau 1272

Maung Thaw Ka - 400 Years of Dreams and the Battle of Tai Yau 1272

Couldn't load pickup availability

400 years of dreams

The President was very angry. The 26th President of the United States. Theodore Roosevelt was particularly angry that morning because he had received a letter of resignation dated February 12, 1907 from John F. Stevens, the engineer-in-chief who had been assigned to build the Panama Canal, connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, across the Isthmus of Panama. The engineer-in-chief had given up. Roosevelt had assigned Stevens to build the Panama Canal since 1905. More than $40 million had been spent on the project.

The Panama Canal, the narrowest part of the Panama Canal in Central America, has been a dream of mankind for 400 years. One of the Europeans, the Spanish military leader Don Carlos, climbed the Darien peak and looked down from the peak and was amazed to see the vast Pacific Ocean on the other side. He was the first European to see the Pacific Ocean. At that time, Europeans did not even know that the Pacific Ocean existed. Since Columbus, Europeans have thought that by discovering America, they had found the end of the world.

The President was very tired. Stevens had already resigned as the Engineer General. Finally, he called in Secretary of Defense Howell Tuff and said, “Now… I’m going to put the military in charge of the Panama Canal, since no engineer can do it.” That night, Major George Washington Gothel, a 49-year-old from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, was called to the White House and given the task of successfully drilling the Panama Canal.

Even the French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, who built the Suez Canal, underestimated the difficulties of the Panama Canal. The region, which rains 250 days a year, the vast, humid forests, the mud, the mosquitoes, the ticks, the fevers, threatened any invader. The geographical conditions, the weather conditions, etc. were all very bad. The President asked Major Goethal what difficulties had prevented the project from succeeding. The plain and simple-spoken military engineer bluntly said that he thought it was due to red tape, internal bureaucracy, and the bureaucrats who were building the Panama Canal in Washington. He said that the engineer in charge of building the canal had the authority of a general in command of a battlefield and the right to make decisions at a moment’s notice.

Roosevelt immediately dissolved the old Supervisory Committee and formed a new seven-man committee, with the strict order, "No one is to interfere with Major Gothel, only to assist him, and Gothel alone is the authority."

Goethe managed to get the president's attention, but when he arrived at the Panama Canal Zone, the workers greeted him with contempt. The American press ridiculed the president's trust in him. They laughed. They booed. He was surrounded by enemies.

From the moment he first met with the canal workers, he...

"The workers digging this canal are not soldiers. I am not a colonel in the US Army Corps of Engineers. I am a labor leader like you. Our enemy is nature, the mountains, the water, the soil, and the weather. The biggest enemy is the Culebra Valley and the locks on both sides of the coast. To succeed, we must fight with our collective efforts. Now... let's get to work."

The steely determination and determination of the would-be leader, and the influence he exerted on the workers who saw him in action, grew. They began to respect a man who did not wear a uniform or act like a colonel, but rather wore a white civilian uniform, sat next to a crane operator, and ate his 30-cent breakfast at the same convenience store as him, and listened to the opinions of a worker on the job.

Even the health officials and doctors who fought against the epidemics of jaundice and malaria in the Equator region did not dare to enter their workplaces late. No one dared to challenge Goethe's influence. Every day, a train would travel 47 miles along the tunnels, inspecting them. When his flag-waving train arrived, the workers would all be in a state of excitement. More than 10,000 workers of all races became disciplined and hardworking workers under the leadership of a good leader. They became workers who did not lie, who did not slouch, who did not slouch, who did not slouch.

Goethal's strategy was to use the parallelism of labor in the workplace. Military engineers were assigned to the Atlantic approaches and locks, calling them the "Atlantic Brigade." Civilian engineers were assigned to the Pacific entrance, calling them the "Pacific Brigade."

The most difficult part of the peninsula, the nine-mile-long Culebra Valley, was called “Battle Center,” and civil and military engineers worked side by side. This valley was the heart of Panama’s buffalo herd. The temperature sometimes reached 20 degrees Fahrenheit. The competition between the two sides led to an astonishing feat of effort, such as the ability to dynamite, haul, and compact tons of rock that they had never dreamed possible. Six months after Goethal arrived, they had removed 1,274,404 cubic yards of earth. This was the most they had excavated in three years.

There were no labor problems at Gothel. They were threatened with strikes. But Gothel's steadfast attitude made even the most stubborn and stubborn people bow down. He spent a week listening to every worker's grievances and grievances and taking action. But there were also no two people who were straightforward. Captain Robert Wood, a military engineer, said, "One day I was called in and told that I was being appointed chief supply officer for the Panama Canal Zone. From the day I started, I said, 'Whatever you do here, the day you run out of cement is the day you lose your job.'"

This was the most difficult assignment. It was not possible to store cement in the rainy Panamanian region. It would turn into stone. Therefore, the order was made to wait several days between the arrival of the cement ship from the United States and the actual use of the work. Once, a storm in the Caribbean Sea caused the ship to be canceled. A ship arrived just hours before the cement was due to run out, and Captain Wood and more than 500 workers rushed all night to unload the ship, load it onto a train, and deliver it to the work site in time, so Captain Wood did not lose his job.

But Goethal did not underestimate the hardships of his workers. The amount of cement poured into each of the 12 great gates would have been enough to build the Great Pyramid of Giza. The amount of earth needed to build the Garkon Dam, which blocks the Chagri River, would have been enough to make the entire globe three feet high, circling the equator. The Culebra Valley, which was blasted with dynamite, is 300 feet wide and 120 feet high.

The Culebra Valley was a dangerous place to work. Landslides were frequent. The valley that had been excavated the previous day was found to be blocked by the next morning's work. The most troublesome was the "Golden Hill" hill. In January 1913, just before the successful completion of the work, Golden Hill collapsed, almost completely blocking the Culebra Valley. The commander of the brigade headquarters quickly reported to Gothel, who, after a brief survey of the scene, gave the order, "Back to digging," and turned away.

On August 15, 1914, at 9:15 a.m., the Panamanian-flagged ship "Encontre" entered the Atlantic Ocean through the Garcon Lock and made the first transit of the Panama Canal. The ship was carrying the President of Panama, the American ambassador, and VIPs. Gothel was not among the group. He was dressed in a workman's uniform and rode alongside his railroad car, watching the workers as the ship passed through the canal he had dug.

Thousands of people on the shore waved and applauded as the ship sailed through the canal. A 400-year dream had come true. But Gothel did not receive the recognition she deserved. At the time, World War I was making headlines around the world.

It has been 70 years now. Thousands of ships have crossed the ocean. However, since the beginning of the 20th century, no one in the world could have imagined that one day humans would be able to build ships over 1,000 feet long and 100 feet wide, so today the world's largest oil tankers and aircraft carriers cannot use the Panama Canal.

Dear reader...

You may already know how much the Panama Canal and the Suez Canal, which are 100 miles long and cut through the sand dunes, have contributed to the interests of the world and humanity. What I want to talk about is not the Panama Canal, but the “Kara Canal”. I would like you to look at the map of Myanmar. In Southeast Asia, you can see the Malay Peninsula. The narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula is called the “Kara Peninsula”. Latitude 10 degrees north