စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

Maung Ne Win - Che Guevara's revolutionary experiences

Maung Ne Win - Che Guevara's revolutionary experiences

Couldn't load pickup availability

From Rosario to Cuba

Ernesto Chibuveira was born on the night of June 14, 1928, in Rosario, one of the most important cities in Argentina. At the age of two , he was diagnosed with asthma, an incurable disease that would follow him from school classrooms, to the heart of the Sierra Nevada, and to the jungles of Latin America.

His parents, who were of Irish and Spanish descent , decided to move to Buenos Aires, where they were civil engineers Ernesto Silver ( B ) and Celia de lasagna.

(4) When he was 4 years old, he could no longer bear the weather in Ernesto. His father had to sleep on Ernesto's bed. Because, Celia said, his asthma was relieved when he slept with his head on the bed. Ernesto's illness did not improve. It only got worse. The doctors said that his illness was incurable. They said that he needed a change of climate.

The Guevara family had to move again. They arrived in Cordoba, where the child's condition improved. The disease also subsided. They traveled and moved throughout the province, eventually settling in Alta Gracia.

Before her eldest son turned 8 , the Ministry of Education sent a letter to Mrs. Cuevas. The letter stated that her son, Ernesto, who was 7 years old, had not yet registered for any primary school.

“I wrote back immediately. I am proud of how much they care about their children’s ability to read and write. I teach them their ABCs . They can’t go to school yet, because of this asthma. They only went to school regularly in the second and third grades, but they failed in the fifth and sixth grades. Their brothers and sisters teach them lessons. They learn it at home.”

Then he went to high school. He went to Cordoba every day in a small car full of his classmates. The driver was Celia de la Sana.

He lived in the “Nidia” house in a good part of the city. It was a happy and prosperous time, but later, circumstances changed, and he sold a large farm belonging to his mother on the outskirts of the city and moved to the city. Ernesto had a room to live in and a place to eat. However, his family’s financial situation was no longer so good that he had to find his first job.

He is an adult. He is independent. He is alert. He is a writer. He has become fragmented. After struggling to recover from a serious illness, he practices sports with his brother Roberto and others. In addition to his three brothers, he has three sisters: Celia, Anna Maria, and Juan Martin.

Some athletes still remember Ngwe Bara from the Atalya Sports Club. Sometimes he would leave the field and use a small inhaler. His interest in books and sports helped him become strong both mentally and physically.

In 1940, while still in high school, he became acquainted with Alberto Granado, now a professor of chemistry. Alberto received his degree three years later.

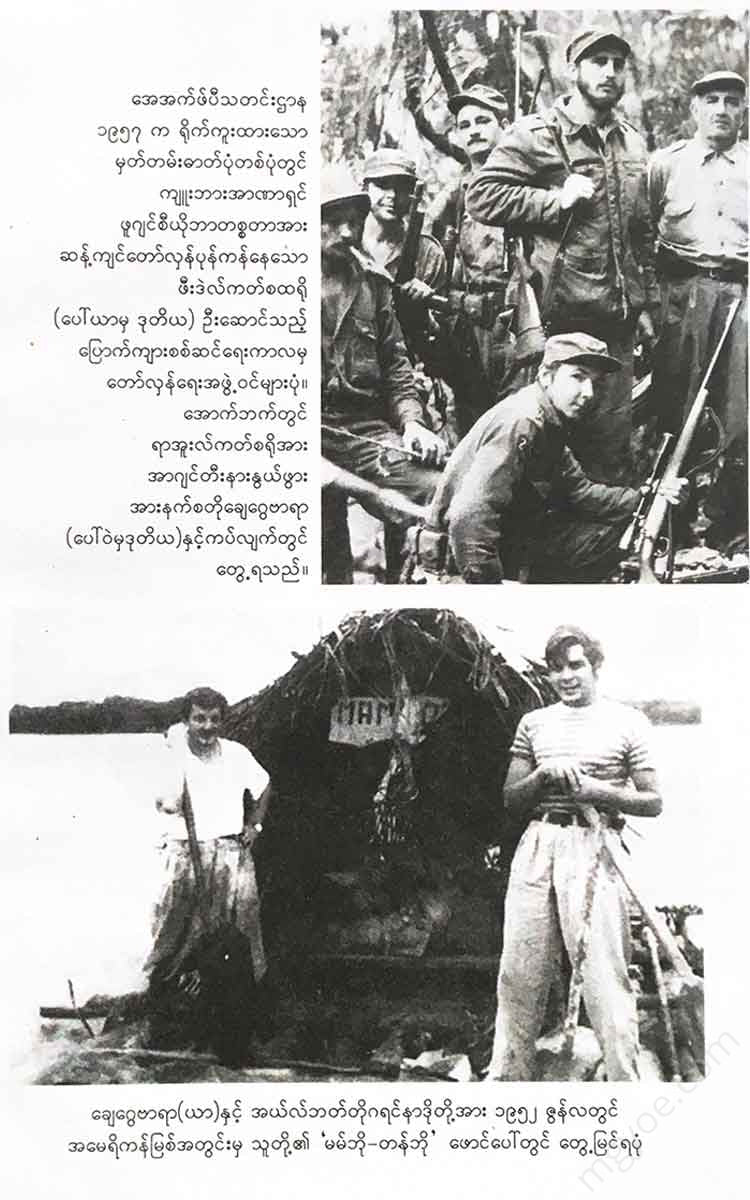

On December 29, 1951, Che and Granado set off on a long journey on a motorcycle. They had decided to travel all the way to the Pacific coast. Guevara wanted to travel all over Latin America. He wanted to learn about this continent. He wanted to discover the ancient civilizations that existed on this continent before the conquerors arrived. He wanted to see the people. He wanted to travel. He wanted to go on foot.

At the end of 1944, the Ngwe Bara family moved to Buenos Aires. Ernesto continued his studies. His interest in mathematics led his classmates to assume that he would become an engineer. However, they were surprised when he told his friends that he had enrolled in medical school.

Before traveling with Granado, he traveled to the north and west of the country, studying skin diseases and other thermal diseases, which interested him. He once traveled from one end of the country to the other by bicycle.

Granado and Ernesto crossed the highlands on foot after arriving in Santiago de Chile. “The journey gave us an opportunity to get to know the people. We worked for a little bit of money, and then we continued our journey. We worked as stevedores, porters, sailors, doctors, and dishwashers. We did everything from picking potatoes to doing other odd jobs. Well , two of us had university degrees and one was about to graduate as a doctor.”

They arrived in Peru. An old dream of visiting a skin clinic had been fulfilled. The group later reached the heart of the Peruvian jungle, where skin patients had built a dam to divert the course of a river that flowed into Colombia.

Problems with travel-related documents, financial matters, and passports also frequently arise.

“In Ecuador, we worked as soccer coaches, earning enough money to buy plane tickets, but Bogota kicked us out,” Granado recalls.

The students saved money and supported each other so they could travel to Venezuela. Granado stayed in Venezuela, while Ernesto traveled to Miami in a cargo plane loaded with horses. He had planned to stay in Miami for only two days, but it ended up being a month. While in Miami, he was very frugal. He lived a simple life, reading in the library and drinking only one cup of milk and coffee a day.

Upon his return to Buenos Aires, he was called up for military service, but was deemed unfit for military service. He was told that he would be called up after graduating.

His extraordinary study, his talent, and his intelligence allowed him to pass ( 11 ) or ( 12 ) subjects in less than a year . He graduated as a doctor in March 1953. He was 25 years old at the time. He was already an active and courageous opponent of all forms of autocratic rule. Seeing the terrible reality of the conditions in which the Indians of Latin America lived, he decided to work for them. He decided to return to Caracas , where Granados was waiting . He intended to work in the Dermatology Hospital in Bolobán.

He left Buenos Aires by train without asking anyone for a penny. When he arrived in Ecuador, lawyer Ricardo convinced him that the place he really had to see was Guatemala.

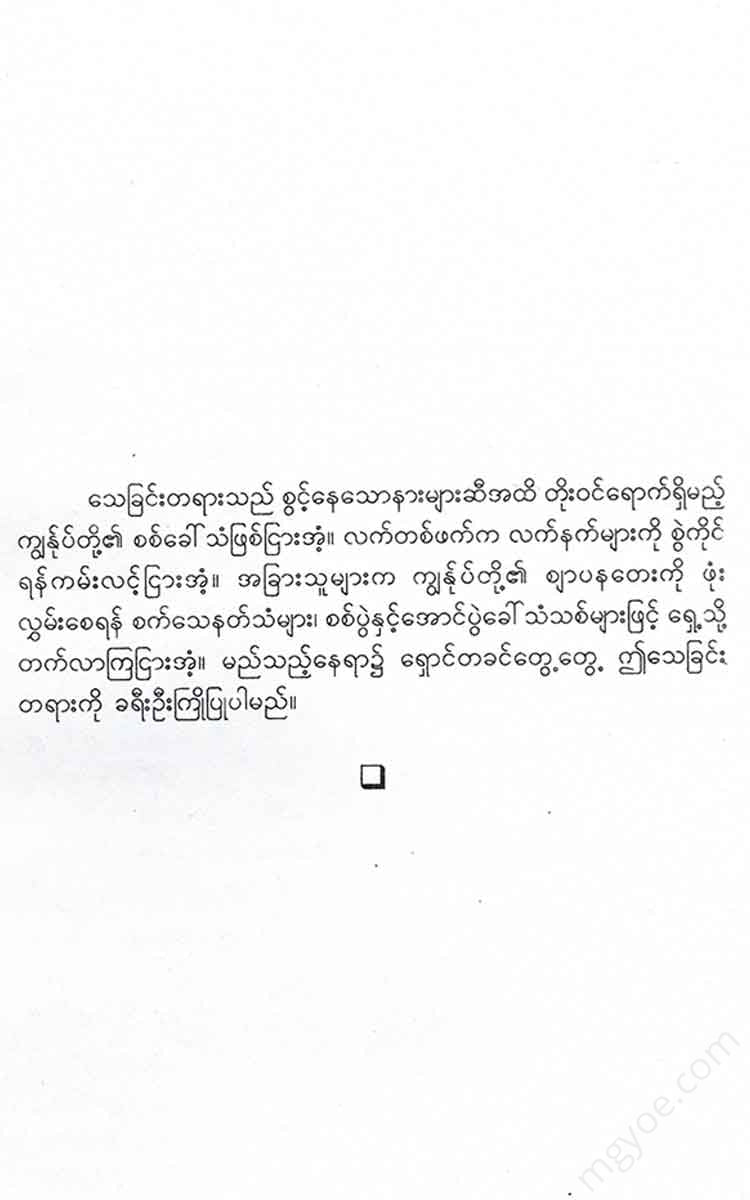

He arrived in Guatemala in December 1953. Then he went to Mexico City. From there he left for Cuba on the yacht "Granma".

(This partial biography appeared in the Cuban weekly "Gran" on October 24, 1967.)

El - Patojo

A few days ago, a telegram arrived bringing news of the deaths of several Guatemalan patriots. Among them was Julio Roberto Casiravel.

In the midst of class wars that engulf an entire continent, the death of a revolutionary in this difficult task is a frequent occurrence. But the death of a friend, a comrade in difficult times, a person with whom one dreamed of good times, is a source of grief for those who hear it. Julio Roberto Barto was also a great friend. He was thin and short. That is why we called him “El Pato.” This is a Guatemalan slang word meaning “little man” or “little man.”

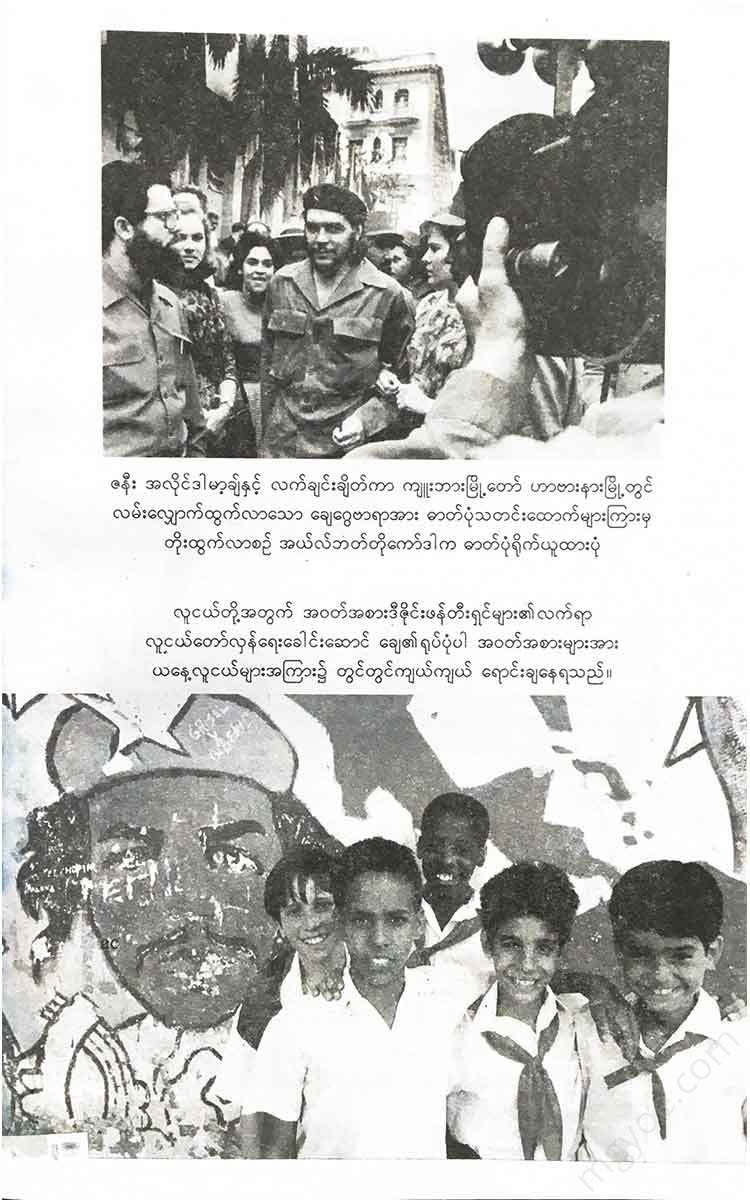

El Patojo, who had witnessed the birth of our revolutionary flame while in Mexico, joined us of his own free will. However, Fidel did not want to drag more foreigners into the struggle for national liberation, in which I had the honor of participating.

A few days after the victory of the revolution, El Patojo sold his belongings and arrived in Cuba with a small suitcase of clothes. He worked in several administrative departments and was the first head of the Industrialization Department of the I, N, A, A ( National Institute of Agrarian Reform ) . But he was not happy with his job. He was waiting for something else. He was looking for a way to liberate his homeland.

The revolution had completely changed him, as it had all of us. This young man from Guatemala, who had not yet fully understood the meaning of defeat, had now transformed into a fully-fledged revolutionary.

We first met on the train, fleeing Guatemala a few months after the fall of Arbenz. We were going to Tapachula. Through it we could reach Mexico City. Although El Patoco was younger than me, we soon formed a lasting friendship. We traveled from Chiapas to Mexico City together. We faced the same problems as the poor, penniless people. We worked together to survive in a strange environment, without hostility.

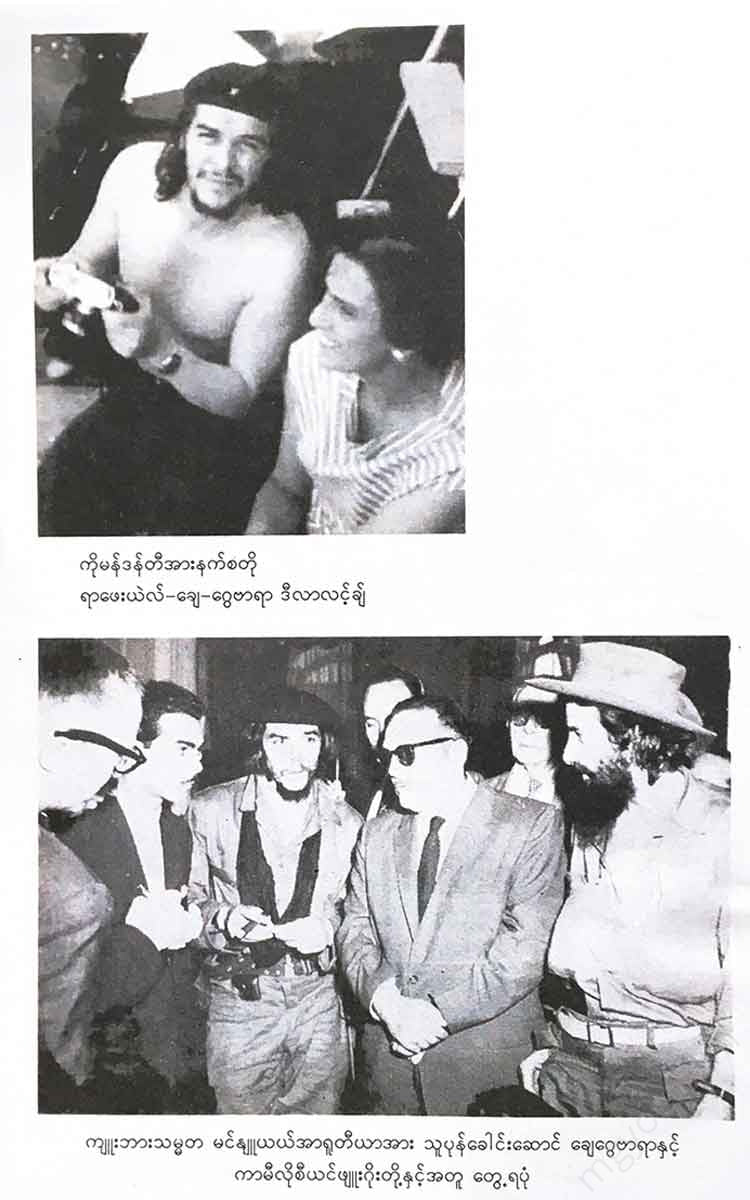

El Patojo had no money. I didn't have much either, so with that money I bought a camera and did illegal work taking pictures of people in the city's parks. The man who worked with us was a Mexican who developed and copied the photos in his darkroom. We walked around Mexico City taking terrible pictures. We had to deal with all kinds of customers. This little boy's picture is so clear.

Therefore, we had to persuade him to give us what we deserved. In this way, we managed to survive for several months. Gradually, the constant events of revolutionary life drove us apart. Did Fidel want to bring him to Cuba? I told him that it was not because there was anything wrong with him, but because he did not want our army to become an international army.

El Patojo was a journalist. He studied physics at the University of Mexico City. After leaving these courses, he returned to them again. He worked wherever he could to make a living. He never asked for help. I still don't know whether this boy, who was as gentle as he was serious, was too stubborn to admit his weaknesses or to approach a friend with his personal problems.

El Patojo was a man of integrity, a man of intelligence, a man of culture, a man of gentleness. He gradually matured, and in his last days he put his great intelligence to work for his people. As a member of the Guatemalan Workers' Party, he was a man who had been disciplined in his life and had become a good revolutionary. Little of his former excessive softness remained. The revolution truly purifies people. It develops. It develops. Just as a farmer, with experience, corrects the defects of his grain and produces a better variety of grain.

When he arrived in Cuba, we lived in the same house, as is customary for two old friends. But in this new life, the old familiarity was gone. I sometimes saw him eagerly studying one of the indigenous languages of his country, and I wondered what was going on in his mind. One day he told me that it was time for him to leave for his mission.

Despite his lack of military experience, El Patojo seemed to honestly believe that it was time to take up his duties. In any case, he was going to return to his homeland to take up arms and fight to revive our guerrilla warfare. At that moment, we spoke at length. We advocated only three things. They were constant movement, total distrust, and eternal alertness. Movement means not staying still, not staying in one place for two nights, moving from place to place without stopping. By distrust, we mean not trusting even your own shadow at first, not trusting your friends, farmers, informers, guides, and contacts, and not trusting anything until you have a liberated area. Alertness means being constantly on guard, constantly scouting, camping in a safe place, and especially not sleeping under a roof. It means never sleeping in a house that can keep you company. These are the lessons of our guerrilla experience that I can impart to my friend, along with a warm handshake. Should I advise him not to do this job? On what grounds could I advise him to do so? We have accomplished something that was once thought impossible. Now he has seen it succeed.

El Patojo had left. Now the news of his death has arrived. At first we expected it to be a name confusion, a mistake. But