Other Websites

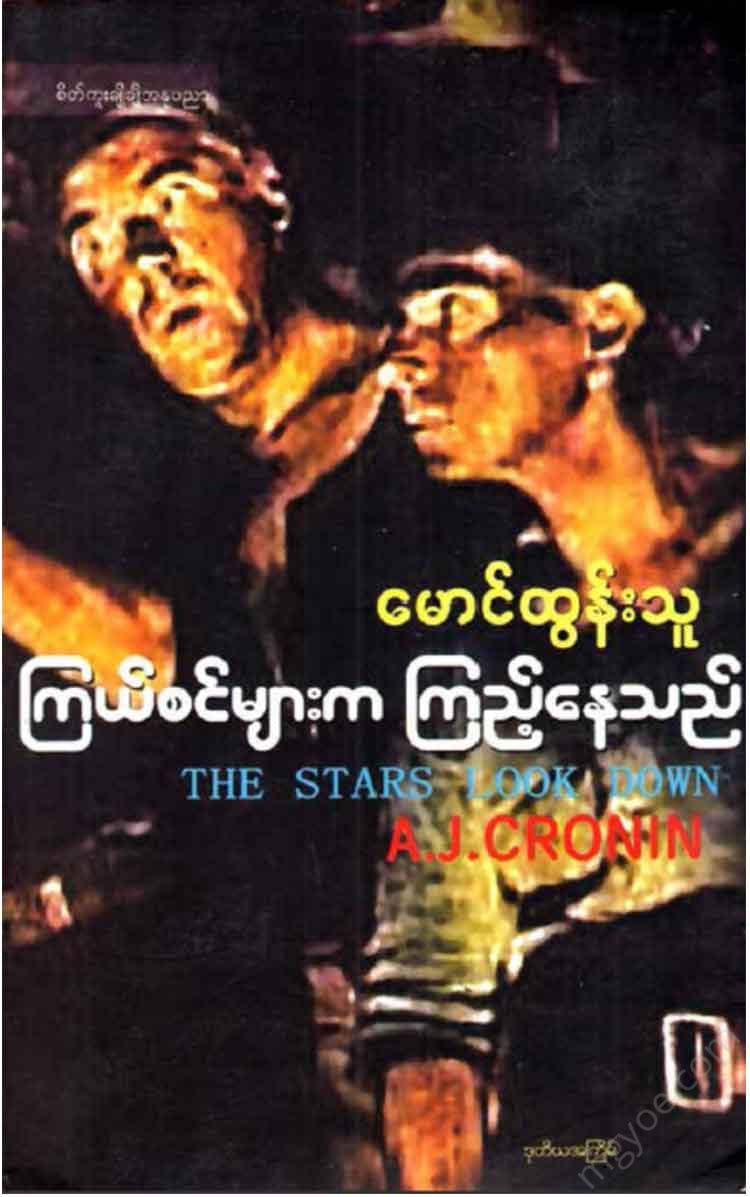

Maung Tun Thu - The stars are watching

Maung Tun Thu - The stars are watching

Couldn't load pickup availability

(1)

When Martha woke up, it was still dark and bitterly cold. The wind, blowing in from the North Sea, was blowing through the cracks in the sloping walls of the two-bedroom house. She could hear the distant crashing of the waves. Otherwise, everything was quiet.

He lay quietly on the kitchen bed. He was as far away from Robert as he could get, having tossed and turned all night, coughing and sneezing. He thought for a minute about the challenges he would face in the new day. He suppressed his frustration with Robert. Then, forcing himself to get out of bed, he got up.

The floor of the hall was icy beneath her bare feet. She was dressed in loose clothes. For a woman not yet forty, she was still full of energy, and her movements were still swift and agile.

However, after changing his clothes, he was still tired from the work he had been doing. He didn't feel hungry, he didn't know why. He hadn't wanted to eat or drink for days. In fact, he was sick. He couldn't even lift his hands. He pulled himself together, walked to the sink, and turned on the faucet. Not a drop of water came out. The pipes were frozen again.

He stood there, pressing his cold hand against his trembling side. He stared out the window at the hesitant dawn. The miners' barracks were before his eyes. All was a blur, one house upon another.

To his right was the dark city of Slyske, a port city on one side and the cold sea on the other. To his left, the head of the 17th mine, Nep Island, loomed over the harbor and the sea, its back to the eastern sky, like a great slaughterhouse.

Martha's eyebrows were furrowed. The workers had been on strike for three months now. When she thought about the suffering of the strike, she felt a change in her mind. She turned around near the window and went to the stove to light a fire. It was difficult to light a fire, she had only the driftwood she had picked up the day before and the coal dust that Hughie had picked up. It was no use lighting a fire with these materials, Martha Finwit always used the good old coal. It was very easy to light a fire with the good old coal and it cooked very quickly. For someone who had been through such hard work, it was frustrating. It was frustrating. But at last she managed to light a fire. She went out the back door and smashed the frozen ice with fury. Then she put it in the kettle and brought it back and put it on the stove to boil water. Boiling water was a waste of time. It didn't boil very well, and as soon as it boiled, he poured the water into a bowl, sat in front of the stove, held the cup in both hands, and took a sip or two. His numb body came alive. It was just plain hot water, so it didn't taste like tea. However, in the current situation, drinking just hot water gave him strength.

He could see the flames from the damp wood. It was because he had torn up an old newspaper and put it in. A piece of newspaper was placed on the stove. He was drinking hot water and reading the sentences on the torn newspaper absentmindedly.

In the House of Representatives, MP Mr. Kiir Hadi asked whether the relevant government had any plans to take action to ensure that education officials were responsible for taking care of and feeding the children, as the problem of homeless children was increasing day by day. The government replied that there was no plan to give any responsibility to the relevant officials.

Martha's thin face showed no interest in the news, no sign of displeasure, and she could see nothing unusual in her face. She turned around quickly. It was as she had expected. Her husband was awake, leaning towards her, his cheek resting on his palm, looking at her. Immediately, a feeling of disgust for her husband entered Martha's mind. Her heart was burning. Everything was unsatisfactory. Everything he had been doing was completely unacceptable.

Then he heard a cough. He thought it was a deliberate cough, out of fear of himself. In fact, he could not separate himself from the cough. If he had coughed, his throat and mouth would have been full of mucus. He propped himself up on his elbows and spat on the newspaper he had cut out of a newspaper.

He always took these papers from the journal. He used his potato peeler to cut them. Whenever he coughed and got phlegmy, he would spit on these papers. Then he would gather them up, put them in the oven, and burn them. Now, when he got out of bed, he would take the papers and put them in the oven.

Martha's hatred for him rose again. She hated not only him but also the sound of his cough. However, she poured hot water into a bowl and handed it to him. He took the bowl and sipped it.

The light has come in. The watch is gone. The first thing he lost was the watch. It was the watch his father had won in a bowling match and given to him as a prize. The watch was a really good watch. His father was a great man and a champion bowler, wasn't he?

He estimated the time. He thought it was about seven o'clock. He took one of David's bags and put it around his neck. He took a man's hat that belonged to him and put it on his head. Then he put on a tattered black coat. When nothing else mattered, this tattered coat was a useful thing. She was not a woman who wore a headscarf. She had never been fond of it. She was a woman of honor. She had lived her life with honor, hadn't she?

Without a word, without looking at her husband, she walked out the front door. She braved the strong wind and walked along the main road towards the city. The cold outside was even more intense. It was frighteningly cold. In the rows of houses that lined the slopes, not a single person was seen, she crossed Seleucia and Middle Ridge streets and passed in front of the Science Institute.