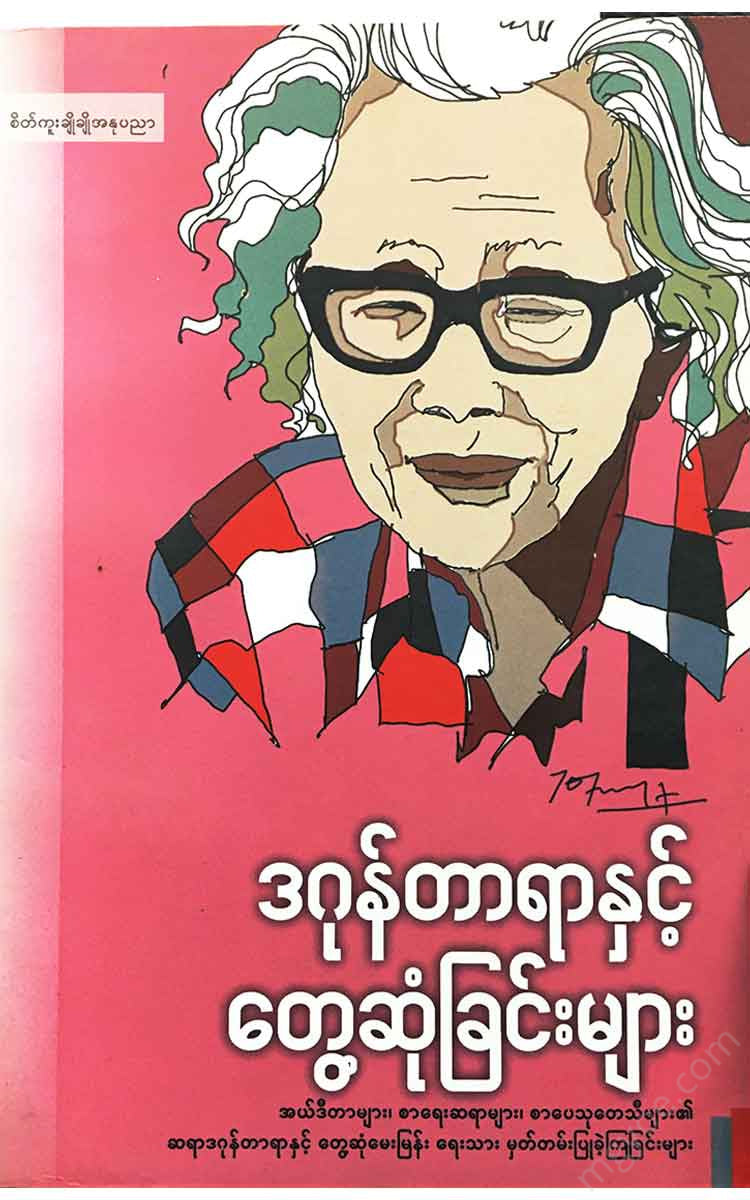

စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

Encounters with Dagon Tara

Encounters with Dagon Tara

Couldn't load pickup availability

“Poetry is the sound of a heartbeat,” Dagontara often says.

"What is a heartbeat?"

"I think you could call it a feeling. You feel the events that hit you, the sounds that hit you, the colors that hit you. And how you respond to that feeling, that's what poetry is, right?"

The old tea ceremony in the Taiku Myittan Village, Dagon Thara’s birthplace, suddenly came into focus. A man named U Htwe Gyi, over 70 years old, with a green head, sipped tea, turned to talk to this person, turned to talk to that person. And I could see that his green head was also moving and swaying. The green head, which was different from any other green, would strike a child’s heart. The child could not bear the impact of the strange green movement and saw U Htwe Gyi’s green head hit him hard and run away.

Whenever I hear about Dagontara's color sensation, the color sensation of U Htwe Gyi, with his green head and the long hair of Dagontara's son Maung Htay Myaing, appears in my mind's eye.

Dagon Tara had a passion for color. He painted. He added colors to his poetry. “Ruby juice,” “Gauguin red,” “Walt Disney blue,” “Rose lava,” “Golden yellow,” etc. When he used the term “Walt Disney blue,” writers ridiculed him. He dared to express the blue he felt as he felt it. Thein Pe Myint once wrote about him, “Dagon Tara claims to be a people’s literature, but he is a fool in inventing words.”

Dagontara writes novels. He writes Ma Vaithu, Kya Pan Re Sin, A Night of the Moon, and many short stories. However, Dagontara is not a novelist, but a poet. A poet is always looking for words that can perfectly capture his feelings. If a word can absorb all his feelings, that word is no longer an English word, a Russian word, or a Chinese word, but becomes the poet's own word, and he cherishes it as if it were his own child. However, those who are lacking in poetic talent and those who do not see Dagontara as a poet criticize him.

What Dagon Thara wrote Dagon Thara's feelings were poetry. Dagon Thara was a poet. From 1934 to 1938, Dagon Thara was his own poet. He was the one who composed the words of Nawaday, Nat Shin Naung, and U Toe. While working in the Rangoon University Student Union, Dagon Thara found friends who were interested in politics and socialism, and he abandoned the Yatu Poda Sora and began writing new poems.

"The poor and the destitute,

They will rebel and gather their troops.

A rich man's arse

If you attack and approach the modern era,

You have turned the whole river upside down.

When the commonwealth was established

"From a communist land..."

(Leka Amon Kavya, Owe Magazine, 1939) | The common ideology became the impetus for Dagon Tara's poems. Due to this impetus, Dagon Tara became a literary leader among poets and writers in the post-World War II era. After the Second World War, patriotism and love for the country were no longer enough for the Burmese people. There had to be patriotism and love for the country, and there had to be class consciousness. Similarly, there had to be a class consciousness in the literature of Burma. To fulfill this need, Dagon Tara single-handedly published Tara magazine.

The Tara magazine published by Dagon Tara had a profound influence on the post-war youth. Poetry lovers were intoxicated by the poems of Dagon Tara and Kyi Aye, which were different from the modern poetry. Fiction lovers were also amazed by the unique short stories of Dagon Tara, Bhamo Tin Aung, Mya Than, Kyi Kyi, Saw Oo, Kyaw Aung, Lingyonee, and Ye Khaung. Tara magazine was published on a political basis, but it was not a political magazine. It was a magazine that experimented with how politics could be combined with art.

Although the publication of Tara Magazine was discontinued in 1950, the attack on the new literary ideas of the youth presented through Tara Magazine was still fierce. Dagon Tara was attacked head on. When there was opposition, Dagon Tara was cool and active. In the same year, he formed the “Art and New Literature Club” and served as the chairman of the club. Even in 1950, when there was a lot of noise against Dagon Tara, he became the chairman of the Writers’ Association, receiving applause and encouragement. In 1952, Dagon Tara was elected as the vice-president of the World Peace Congress (Burma). He attended the Asian Writers’ Conference in 1956 as a representative of Myanmar writers. He often attended the World Peace Council conferences held in Asian and European cities as a representative of Myanmar. He also actively participated in the establishment of the Myanmar Writers’ Union and the Myanmar Poets’ Union.

[2]

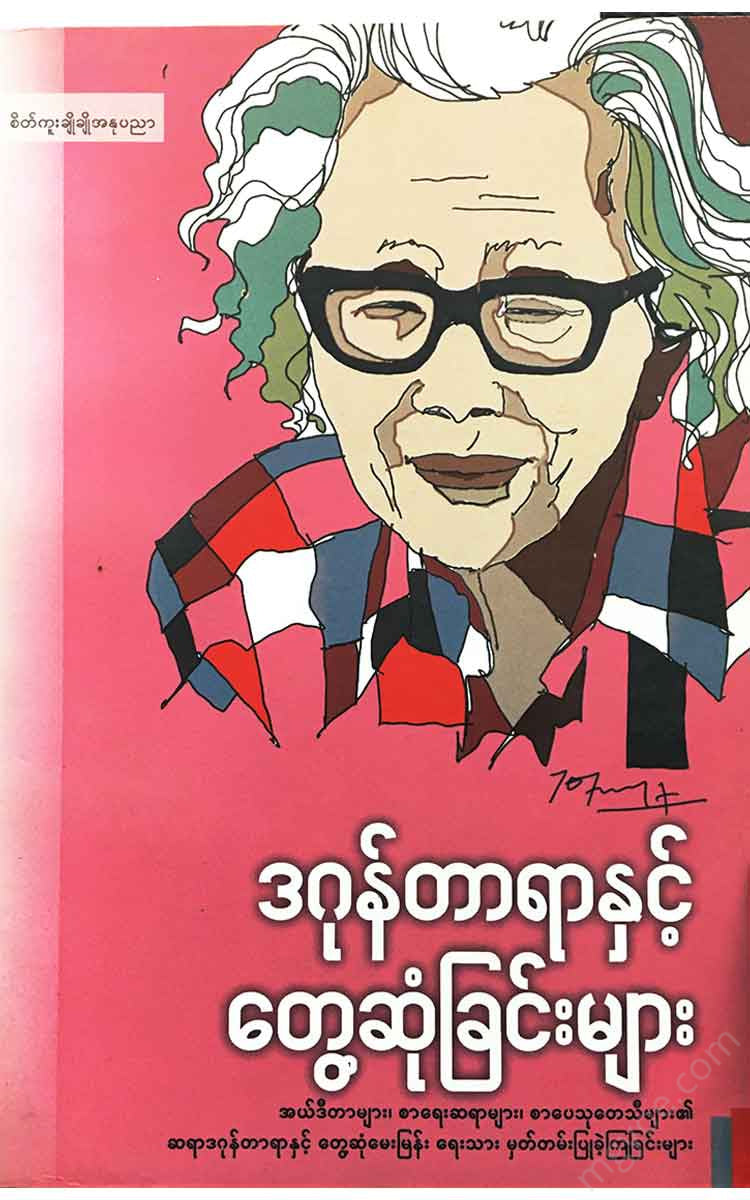

The artist San Toe once painted Dagon Tara’s symbol on the jacket of his book “Literary Theory, Literary Criticism, Literary Movement” with a curly, wavy head of hair and thick, dark glasses. Dagon Tara’s friends also noticed Dagon Tara’s unique hairstyle, just like San Toe’s. His hair was like a combination of waves and curls. His broad face held his loose hair up and down. Whenever I talked to Dagon Tara closely, looked at his face, and listened to him speak, it seemed as if he had thought out his words before speaking. When he spoke, he was very weak. He moved his limbs slowly. He seemed to prefer soft, strong colors to bright colors.

Dagon Thara's poems emphasize the unity of the group. They emphasize feelings and thoughts. They also use artistic groups. If rhyme interferes with his thoughts, he rejects the rhyme system. He believes that the four-syllable rhyme is the most extensive form in poetry. If his four-syllable rhymes are recited orally, they are tongue-tied. Dagon Thara believes that modern Burmese poetry is not meant to be recited, but to be read and enjoyed with the eyes. However, he says that his poetry can be played on the piano. In his poetry, new metaphors, new images (imaginary images), and new symbols are often found that are consistent with the subject matter.

Moe Wai Literary Magazine, May 1970.