Other Websites

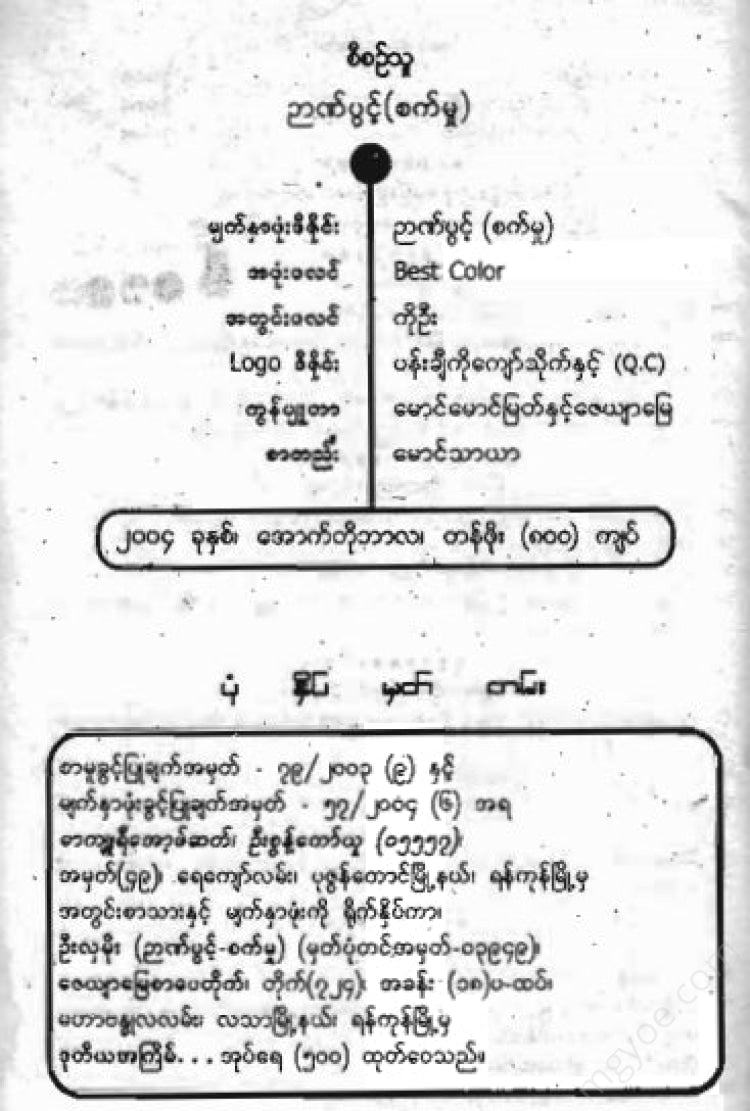

University of Nandamuri - Imphal Battle

University of Nandamuri - Imphal Battle

Couldn't load pickup availability

( 1)

Two boxing champions....

One is English, one is Japanese,

In the first round, the Japanese boxer knocked out the English boxer, who had long held the world title, until he was thrown to the side of the western bank of the Chindwin River, which looked like it was outside the ring.

The setting is Burma. The time is (1942).

The Japanese, who had made a bold move onto the world boxing stage, used illegal elbows and knees to defeat the English boxing great, who had won the prestigious title of imperial champion, in the first round with a knee to the groin.

By the second half of 1943, both Letwei Kyaws were preparing for the second round. In 1943, the Japanese had conquered all of Burma much sooner than they had anticipated, and by May of that year they were faced with the dilemma of whether to defend the conquered Burma and remain on the defensive, or to continue their advance into India and launch an offensive.

Some Japanese generals urged an immediate attack on Assam, the northeastern gateway to India.

However, the British, who had retreated to India, threatened to attack Rakhine, so they hesitated to implement this proposal immediately.

Again, towards the end of 1942, the idea of attacking and capturing Imphal, which was centered on central Burma and mainland India, arose.

The Imperial Army Headquarters in Tokyo and the Japanese Southeast Asia Command in Singapore readily accepted the idea.

The 15th Japanese Army in Burma was tasked with developing a plan to attack and capture Imphal.

Proponents of this idea argued that the British were not well-prepared for a defensive position and that Imphal was a key point for counterattacks against central and northern Burma.

These statements are indeed true.

However, two Japanese generals who were specifically responsible for the battle of Imphal strongly opposed the immediate continuation of the attack on Imphal.

They objected on the grounds that there were no railways or roads to allow their troops to march in large numbers, and that the roads were blocked by thick forests and mountains, and that disease was rampant in the area. These reasons were also true. Of the two generals who objected so strongly, Mattaguchi would later become the most important figure in the Battle of Imphal.

Thus, the issue of whether to immediately attack Imphal was left hanging between the two sides, and the Japanese 15th Army had to bide its time on the defensive until the end of 1942.

As the year 1943 approached, there were reasons for the Japanese authorities to reconsider their plans for the invasion.

In January 1943, the Tsimshita Division, led by Brigadier General Wingate, penetrated through a vast wilderness that everyone thought was too difficult to cross, into central Japanese-held Burma, and operated behind enemy lines.

The Japanese military authorities were concerned that this movement was a prelude to a major British offensive. In northern Burma, the Yunnan Chinese Army, which had been driven out in 1942, was also gathering men and weapons and trying to reopen the China-Burma highway with American help. In Manipur, the British were establishing a large base on the Imphal plains, building and expanding roads from Imphal to the east and south, and expanding and renovating old airfields near Imphal.

These three reasons point towards the same goal.

It was an Allied counteroffensive.

Japanese military authorities believed that the Allies would launch a counteroffensive against Burma as early as 1943.

Wouldn't it be a good idea to start by destroying Imphal, the base of the Allies that will launch a counterattack on Japan, before it becomes stronger than it is now, to prevent the next danger?

To address the new situation, the military authorities in Burma were reorganized.

In the new organization, General Kawabi would be responsible for the overall command of Burma, controlling and administering the Japanese forces in Burma and Rakhine, and the 15th Japanese Army would be responsible for the central, northern, and Yunnan fronts.

The appointment of General Mattaguchi as commander of the 15th Japanese Army in the reorganization of the Japanese military authority in Burma was a rather unusual move. Mattaguchi, 56, was known for his tough nature, fearsome nature, and a stubbornness that made his subordinates tremble.

Mattaguchi's 15th Army consisted of three divisions: the 56th was responsible for monitoring the Chinese forces in Yunnan, the 18th was responsible for the entire northern part of Burma, 250 miles northwest of Mandalay, and the 33rd was responsible for preventing the enemy from attacking Mandalay from the west and northwest through Chindwin. General Mattaguchi had a total strength of 100,000 (one hundred thousand) men, including supplies, medicine, and office staff.

(1942) Mattaguchi, who had strongly opposed the attack on Imphal while commanding a division, became a general in command of an army and began to urge the attack and capture of Imphal without delay.

Mattaguchi calculated that if Wingate's Tsingtao columns could cross the vast wilderness, which he thought was impassable, his (15) Japanese Army, well-prepared and ready to cross at the right time and season, could do so. Mattaguchi therefore persuaded General Wabi, who was the general in charge of the Burma War Zone, to accept his views on the Imphal.

Even then, some members of Kawabi's headquarters and Mattaguchi's headquarters were still opposed to Mattaguchi's plan. They argued that it would be difficult to get enough troops to fight Imphal, and that even if enough troops were obtained, the task of supporting and feeding so many troops from behind would be too difficult.

If we compare the communication routes of the British in India with the transportation conditions of the Japanese in Burma, we will see that the Japanese are still superior.

There is only one road from India to Imphal, but there are many routes from Yangon to Myitkyina and the towns on the Chin River.

Mattaguchi, who was always determined to do something, pushed aside those who hindered his plans and presented his plans in detail, one after another. Thus, the Imperial Headquarters in Tokyo and the Japanese Southeast Asia Command in Singapore gradually came to agree with Mattaguchi's plan.

As the days passed, the Japanese government in Tokyo became more and more supportive of Mattaguchi's plan.

This support is not without reason.

Within a short year of the outbreak of war, Japan had conquered the far-flung Aleutian Islands in the northeast and New Guiana in the far south in the Pacific Ocean, greatly expanding the Japanese Empire.

Therefore, the morale of the Japanese people was greatly boosted by the war being waged by the Japanese government.

However, by the time we moved to 1943, the situation had changed dramatically.

Japan was forced to retreat from the far-flung Aleutian Islands, and in the South Pacific, Japanese forces were being crushed by Allied Admiral MacArthur.

The Japanese army, navy, and air force suffered continuously in the Gouda Canal, the Korean Peninsula, Midway Island, New Guiana, and other areas. As a result, the morale of the Japanese people gradually declined.

The Japanese government urgently needed a victory to show for its people. A victory from the Burmese side might be a morale booster. This victory should not be a battle known only in the place where the battle took place, but one that Japan would recognize throughout the country.

It was a victory that would cause panic in India and alarm among the Indian government, and it would also stop the British from advancing on northern Burma.