စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

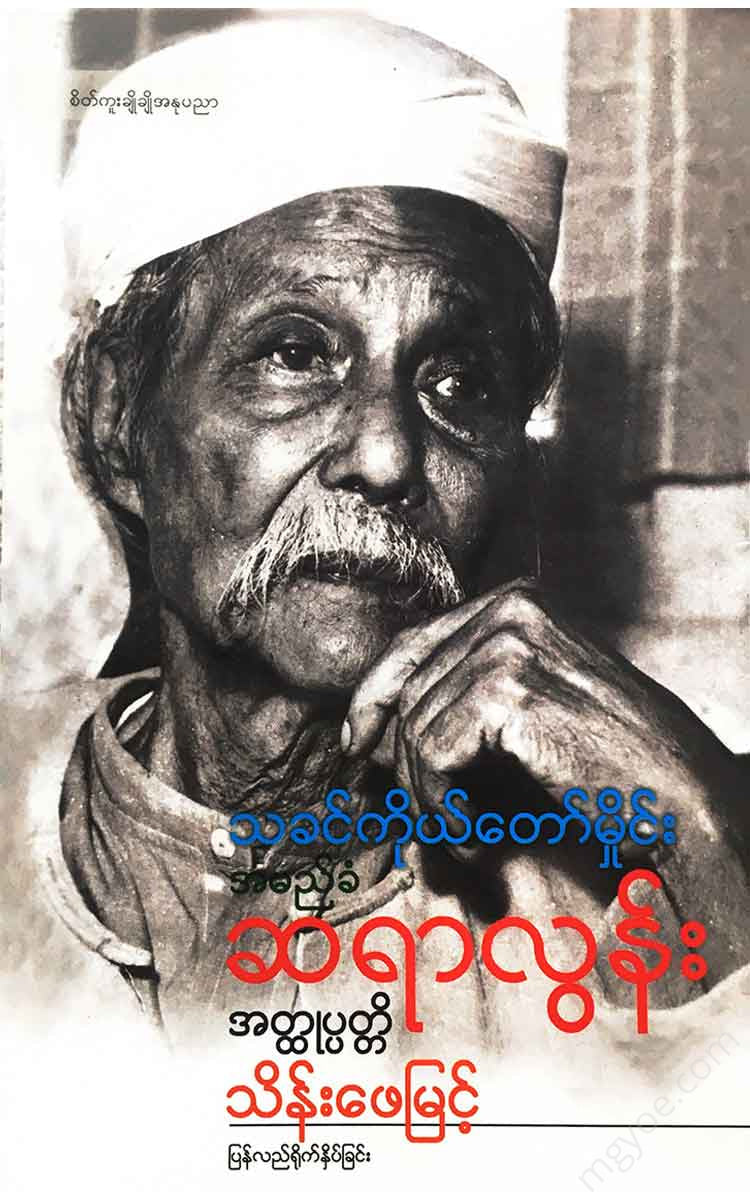

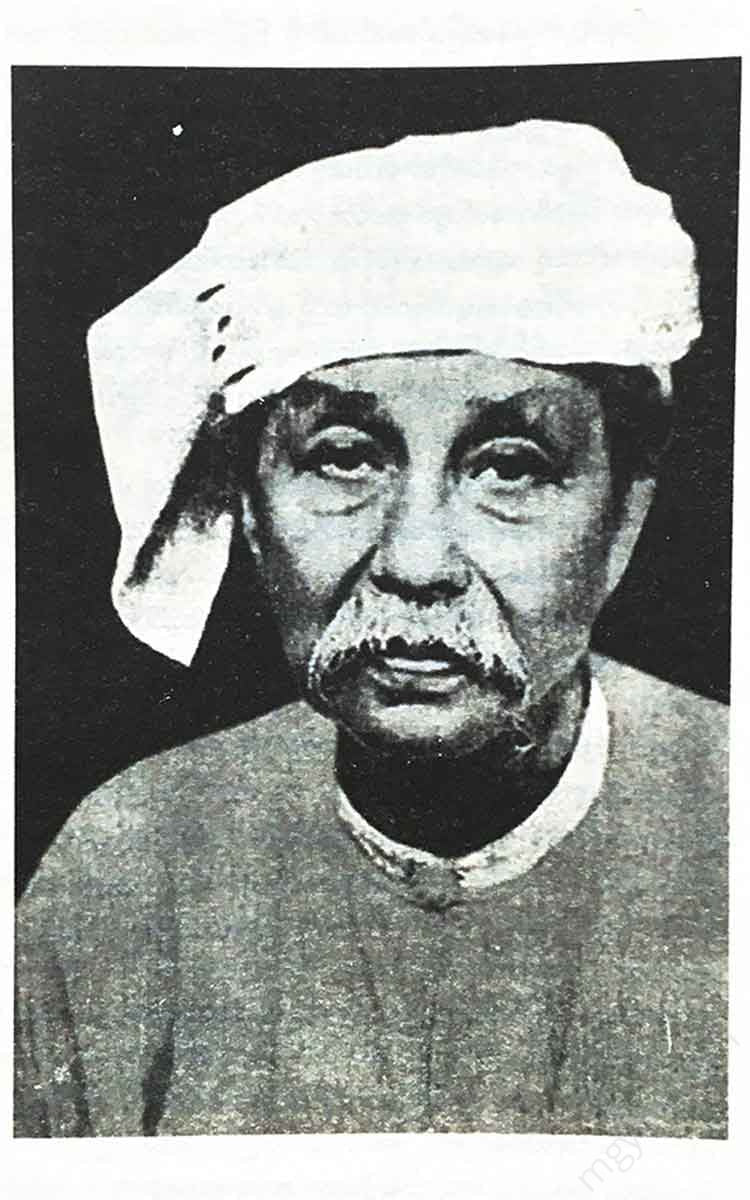

Thein Pe Myint - The Biography of His Holiness the Great Teacher

Thein Pe Myint - The Biography of His Holiness the Great Teacher

Couldn't load pickup availability

If we look at the history of Burmese literature, we will see that the number of pieces of literature written using natural language is extremely small. If we look at Burmese literature and analyze it, we will have to conclude that the Burmese people are the people who have the least natural language (or) do not use natural language the most.

If Buddhism had not spread to Burma, it would not have reached a level where it could be called Burmese literature. The Vedic literature, the Inai, the Mandha, the myths, the

It must be a literature that is still in its infancy. Or it may be a garden of literature that is cultivated with innate wisdom, but now, due to the spread of Buddhism, it is a secondary literature that is lacking in innate wisdom (or) that is not allowed to use innate wisdom.

The Magadha language (वा), which brought Buddhism to Burma, is also widely known as the Pali language (वा), and Buddhist literature is also extensive and complete, and it was sufficient for the ancient people, so Burmese writers did not need to write with their own intelligence. There are poems praising the forest, such as the poem praising the Himalayas from Vaisantara, the poem praising the return of Kaludaya to Kapilavattya, etc. There is also a poem about the wandering of a maiden, which the great sage himself wandered. The villager is depicted as a worm, and the king of Janaka is depicted as a man who has abandoned his wife. If you want to write about the moon, there is a story about the king of the moon, the Samanyaphala Sutta, and if you want to write about the conversation between the king of the moon and his wife, there is a story about the conversation between the king of the moon and Mallika Devi in the Kosala Samyota. If you want to write not only about the drama, but also about the ten-level drama, the five-hundred-and-fifty-level drama, etc. If you want to write about a man who is wise and intelligent, and if you want to write about a hero who is brave and courageous, there is the Mahajanaka. If you want to write about a beautiful woman, there are the Amaya and the Ming. If you want to write about the next chapter, there is the Kusajatka. Thus, the great Buddhist literature, which is a great tree that can be sweetly obtained, has already borne fruit, but the Burmese were content. They hid their original wisdom and it rotted. If someone dares to use their natural intelligence, they are ridiculed and called a child. They are condemned.

The ancient Burmese also breathed in Hindu influences with great pleasure. They mixed the Vedic-Inai mantras and the legends of the ascetics with the opposing Buddhist teachings and wrote them down. They even wrote Kamasattu texts. They even adopted the “Sanskrit” texts of the Ceylonese, which they inherited from the ancient Hindus, as if they were the words of the Buddha.

In ancient times, there was no printing press, it was difficult to copy on paper, there was nothing to write on except leaves and boards, and blackboards stained with charcoal. If a Burmese scholar could not go to the Golden City, he would starve to death, and if the king did not use them, he would be cut off. In ancient times, Burmese scholars could only look to the palace in the Golden City. In order to please the king, the king would praise him by saying, "The king is angry and knows his mind," so the scribes usually wrote only what the king liked. How to respect the king, how not to tread on the ground when the king calls him (see the special advice of Saint Kyaw Tu), how to raise the king's sons and daughters (see the golden ear-rings). How to accept everything the king does without resisting, etc. They wrote in various groups. The Burmese kings in Burmese history also praised the writers who best flattered them, the writers who most enslaved the people of the country, (including historians) the writers who helped them in courting their wives (see Zeyaranta Meik-shin Thankho, Myawaddy King U Sa, etc.) In short, only the noble writers were honored, so only the writers who pleased the king flourished. Burmese literature was the literature of the nobles and the rich, not the literature of the poor Burmese people.

Although the writing methods have changed, from prose to verse, from song to verse, from ballad to verse, from verse to verse, from verse to verse, from verse to verse, from verse to verse, from verse to verse, from verse to verse, from verse to verse, from verse to verse, etc., the writing methods have changed, but the subjects have not changed. The five virtues of women that the Maharatha Shara praised in poetry were written in poetry by the Thankho Nat Shinnaung, the Myawaddy Minister in poetry, and U Punya in poetry. In the Inwa period, the Maharatha Shara and the Thila Wana Sa wrote poetry based on the Dhamma Nipat. The latest Mongyalman Sayadaw also wrote poetry based on the stories of the Buddha. U Toe wrote a poem based on the Rama story from Hinduism, and U Shwe Ni, the great interpreter, wrote a poem based on the stories of the Buddha. The chief minister of the Dwinthin district, Maha Sithu, and the monk Taung Phila, wrote the Vaisantara, while the others, U Kyen U and U Punya, wrote plays. U Thas promoted the king with a pulika khas echin. U Punya promoted the king with a maukon. There was no significant improvement.

In Burma, there were few writers who rebelled against literature. When Buddhism was flourishing in Bagan, the era of secular literature was flourishing, and in order to make people understand that secular affairs were also important, Saturangabala, a wise man of the Pinya period, wrote the book "Loka Niti" and the "Hitopa Veda" and rebelled. (It is not clear whether it can be included in the Burmese press because it is in Pali. However, the author is Burmese.) While the Pali language was flourishing, Anantashuriya rebelled by writing Lanka in Burmese. The Maharathasara and the Thilavansa rebelled by adding secular references and lessons to the Jatakas. The monks still scolded the great sage, saying that he wrote poems and poems that were not worthy of a monk.) But Uttama Kyaw, without paying attention to the king, lived in the forest and rebelled against the tradition by writing a poem about the forest, relying on the praises of Kaludhara.

It is strange that when the Inwa Dynasty fell and Burma fell into the hands of the Talai Dynasty, no revolutionary writers appeared.

Then U Hlaing, the secretary of the government, rebelled by not doing what the king wanted, but writing boldly and saying what he thought was right. Many called U Hlaing arrogant. Saya Pe

He was also a brave and rebellious man.

During the reign of King Mindon and King Thibaw, the Yap Lalu Dharma appeared. The teachings of the Kyabing and U Punya appeared, as if they were singing in a melodious voice.

Then, in Burma, chaos broke out, and during the Mandalay era known as the Yadanarbon period, the fallen monk Sein Zani U Thila Sara preached in a melodious manner.

When the British took over Burma, the Burmese scholars remained silent. The chief monk wrote letters of rebellion. (See the book "The Dog of the Lord") The monk Sibani wrote jubilant poems and expressed his sorrow. However, the monk's letter, which initially aroused patriotism, ended with the words "You have become such a slave because of your past karma, do not be sad," and the little heart that came up fell back as if it had been hit on the head with a big club. Maung Taung U Kyaw Hla also did not rest and did not give up, but composed letters of rebellion with iron. However, the patriotic feelings that came up were only expressed in the words of the fortune teller, and the patriotic feelings that came up were lost in the events of the Maung Thant assassination and the Thayarwady rebellion.

Rebel writers of the English era

Burma was destroyed until the students' strike in 1920, but no other writers except U Kyaw Hla were heard to have emerged. The kind of writer who wrote the "Aung Su Oba Mingalar Kyaung Taw Ten Paara Jutu" that young students sang, the kind of writer who wrote the "Shwe Na Daw Achin" by the Prince of Wales, the kind of writer who wrote the "Marana Nussati Mawkun", the kind of writer who wrote the "Kya Pa" by the poet