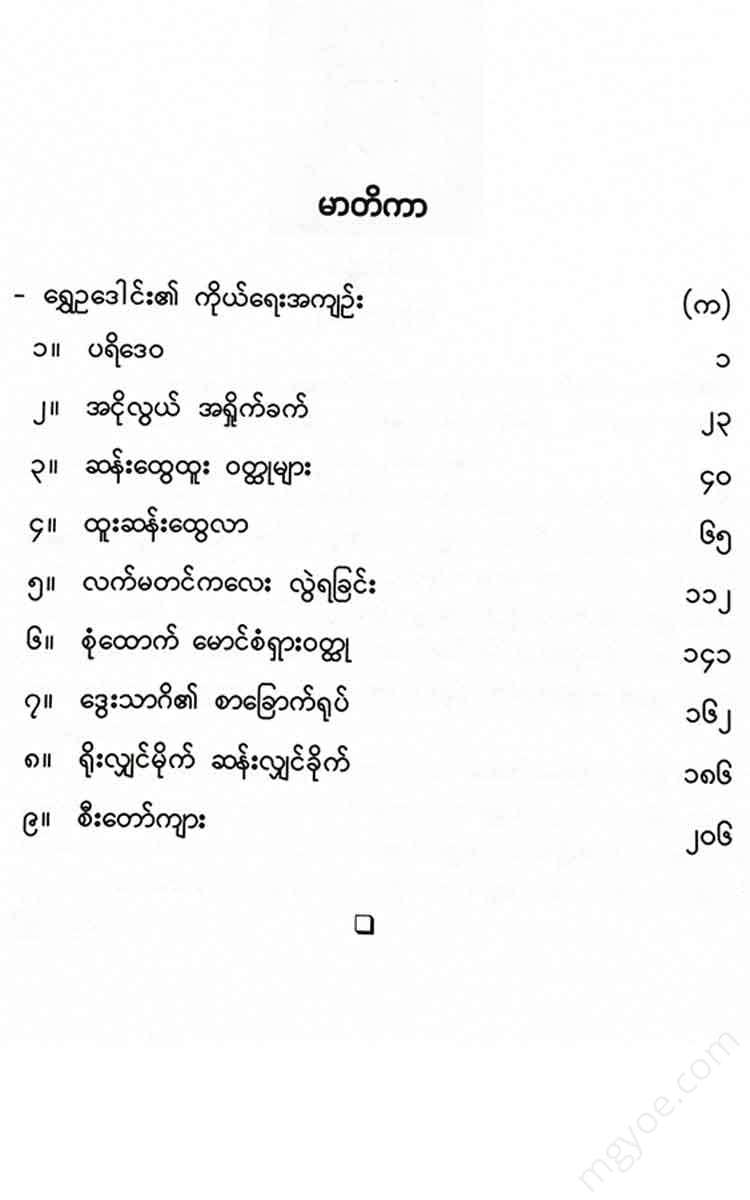

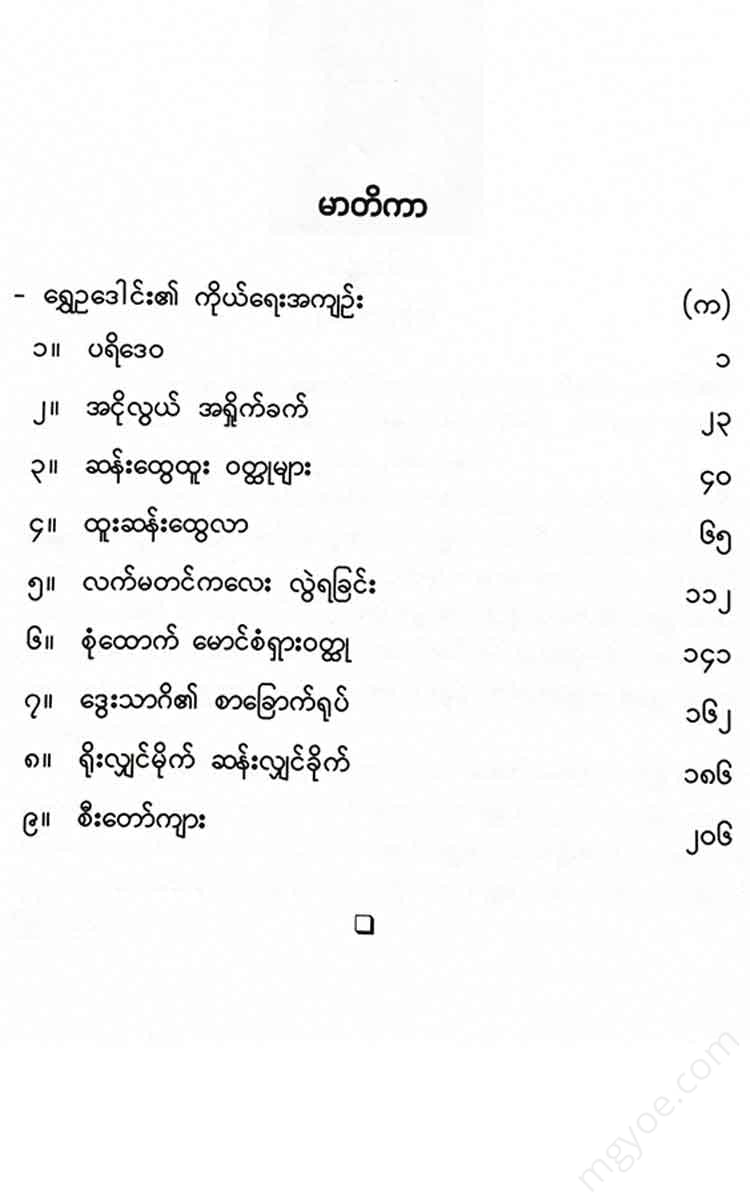

စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

Golden Peacock - Strange and Miscellaneous Short Stories

Golden Peacock - Strange and Miscellaneous Short Stories

Couldn't load pickup availability

Parideva

At a certain consecration ceremony, the Venerable Samuti Sangha had given a detailed discourse on the benefits of offering alms to themselves and the benefits of introducing their own sons and the sons of others into the Buddha's teaching. After each of them had departed with their offerings, some of the remaining male and female congregations were busy with their own affairs regarding the offerings, while others, including the men, women, and the nuns, were discussing and consulting on the Three Jewels.

While they were discussing this, a Buddhist monk, who was about 50 years old, said, “Death is more difficult than life.” It is not very difficult to understand society and human affairs in this world. When we die, we should practice so that we do not become food for the four elements, but at least go to the heavens and the earth. Then, they talked about the various types of death. The first Buddhist monk said that among all the types of death, sudden death by one’s own weapon is the worst and most vile death, and the promise of future rebirths is only a fraction of the four elements, and that we can die in the same way for “500-5 worlds.”

Then, without saying a word, an old man, who was leaning against the pillar of the pavilion and smoking, and who was about 70 years old, with a mustache and hair that were white, said, "No matter how or with what weapon a person dies, what is his fate? It is impossible to determine whether he will fall into hell, go to the grave, go down, or go up. It is impossible to know what kind of concentration the soul will have on the verge of death. For example, if a person stabs himself with a sword and kills himself, the soul will not have fallen at the same time as the stab. The mind is very fast, and since it can go through many different phases from the time of injury until the time of death, it is difficult to determine the fate of that person precisely." Then, a man, When the female audience asked the Buddha to speak about this in Pali, the old man recited the following in the Mizzima Nikala and Uparipanna Pali: Venerable Vaggali, Venerable Sanda, Venerable Gausika, and others, who had ended their lives with swords and weapons, and who had passed away after having been stabbed with them; among them, Venerable Sanda, who had stabbed himself with a sword, spear, or rope, had only remembered when he saw the bad omens of his own life, and had practiced the Dhamma, and had attained arahantship, and had passed away at the same time; and when he spoke in Pali, the audience was very surprised and praised him for this.

Then the men and women in the audience spoke one by one about whether one should or should not kill oneself, whether one should or should not kill oneself, whether one should or should not kill oneself. The old man, who had been listening quietly while smoking, put down his cigarette and asked permission to speak. All the Anantasatavas considered death to be the greatest of all evils, and were afraid of death. Therefore, only the person who killed himself with his own weapon could decide whether it was right or wrong. In connection with this, he told the audience about an incident that he had personally experienced that was very strange and surprising, and when the audience heard it, it would be very difficult for anyone to decide whether it was right or wrong to kill oneself. The old man was very old in age, very intelligent, and very knowledgeable about the local area. In connection with this, they asked for forgiveness and wanted to hear many stories about the events that the old man had experienced. The old man replied as follows.

( The old man's name was U Soe Gwang, so the events he experienced were not told orally to the audience, but in writing.)

In the year 1240 of the Burmese calendar, our King Thibaw succeeded his father, King Mindon, to the throne. About a year after his accession to the throne, I traveled in a rowboat along small rivers and streams, such as Mae Za Stream and Shwe Li Stream, which were still relatively uncrowded at that time, and then made a living by selling goods and textiles in the small villages and hamlets along the stream banks. While I was doing this business, I met a friend from my school days, Maung Aung Baw, in Shwe Li Wa. He was a man of considerable wealth and I asked him what business he had in the upper villages. Maung Aung Baw replied, "Is it true that I have heard that wild elephants are very numerous here?" I replied that wild elephants are very numerous here, and that sometimes, when we travel by boat or canoe, we often see herds of 70-80 to 100 wild elephants coming down to drink water on the banks of Shwe Li Creek. Then Maung Aung Baw took out a small paper from his pocket, spread it in front of me, and showed me a page that looked like the map that the British government had just printed. Then, pointing with his hand to the place where the Shwe Li River flows, he asked me, "Isn't this the place where the Shwe Li River flows?"

Then, after I had looked at his map for a while to understand it, I answered that I did, and Maung Aung Baw pointed to a place to the north of the river and asked how far it was from the source of the river. Then I told him that, judging by the length of the river, I thought it was about 100 Burmese poles (200 English miles), and Maung Aung Baw asked me if I would go with him to that place. Then, when I told him that I could go anywhere if it was profitable, Maung Aung Baw said that if I went with him to that place and succeeded in my plan, I would give him 1,000 kyats. If I succeeded, I would have enough wealth and money not only in my lifetime but also for my children and grandchildren.

Then I asked Maung Aung Baw if he was a treasure hunter, and I said that the term treasure hunting was very complicated, with monsters, snakes, and dragons, and so on, and I could not trust him very much. Maung Aung Baw said that his work was somewhat similar to that of a treasure hunter, but that he did not dig for treasure or gold or silver. He did not dig for it when he found it. He did not have any guards or protection. When I said that I would explain it to him so that I could understand. Then Maung Aung Baw heard that there were many wild elephants in this place, and I heard that when the Kachin wild elephants were old and weak, they would go to their graves and die only when they reached their graves. Since elephants have existed in this place and in this area for many years, there are thousands of elephant bones, He said that the elephant tusks were piled up in the elephant cemetery, and although he had never been there himself, he told Maung Aung Baw about the route and the journey he had heard about. Maung Aung Baw had calculated and written down the route along with the map. Maung Aung Baw had brought 3,000 kyats of silver from the inheritance he had left after the death of his mother and father as travel expenses. So if I wanted to go with him, if I did not find the elephant tusks, I would give him 1,000 kyats. If I did find them, I would sell them to Lower Burma, which was under British rule, and give me one-third of the money. He also said that whether the elephant cemetery was found or not, it was his responsibility to pay for the travel expenses.

When I told him this, I was about 30 years old at the time, a widower, without children, without parents, and with few relatives, so I had no one to turn to. I had loved Maung Aung Baw since I was young, and I also had a desire to experience strange events. So, regardless of whether I found the elephant tomb or not, or whether I got paid or not, I enjoyed the adventure, and I agreed to go with him.

As soon as we had made that confession, we bought about 10 people's food and water for a month, loaded them onto my boat, hired four boatmen, and set off for Shwe Li Creek the next day of the festival.

Maung Aung Baw was described as a schoolmate of mine, but he was still a student when I was Ko Yin Wut's age, so in fact he was only about 25 years old at that time. Maung Aung Baw was a young man without a wife and children at that time, living a free life. His appearance was fair, with a flat nose, small, deep eyebrows, and a slender body. He was a handsome man. He often studied difficult subjects and literature, and his face had a calm and serene expression, as if he were constantly thinking deeply.

We went up the river with four bamboo canes for about ten days, and arrived at a small village called Kholo, inhabited by the Shan people. This village was the last stop of my journey when I was trading along the river in my boat, and from this village I returned to Song, so I left all my goods and clothes with a friend in the village, and after buying all the food and water I needed, we went up the river again.

The river was very narrow at that point and the water was very fast. The four rowers rowed for about 6 hours a day, and I rowed the boat for about 6 days. When I reached the left bank of the Shwe Li River, I saw a beautiful, young, and graceful 16-year-old girl standing in the water, looking at us intently. The boy was gone.