Other Websites

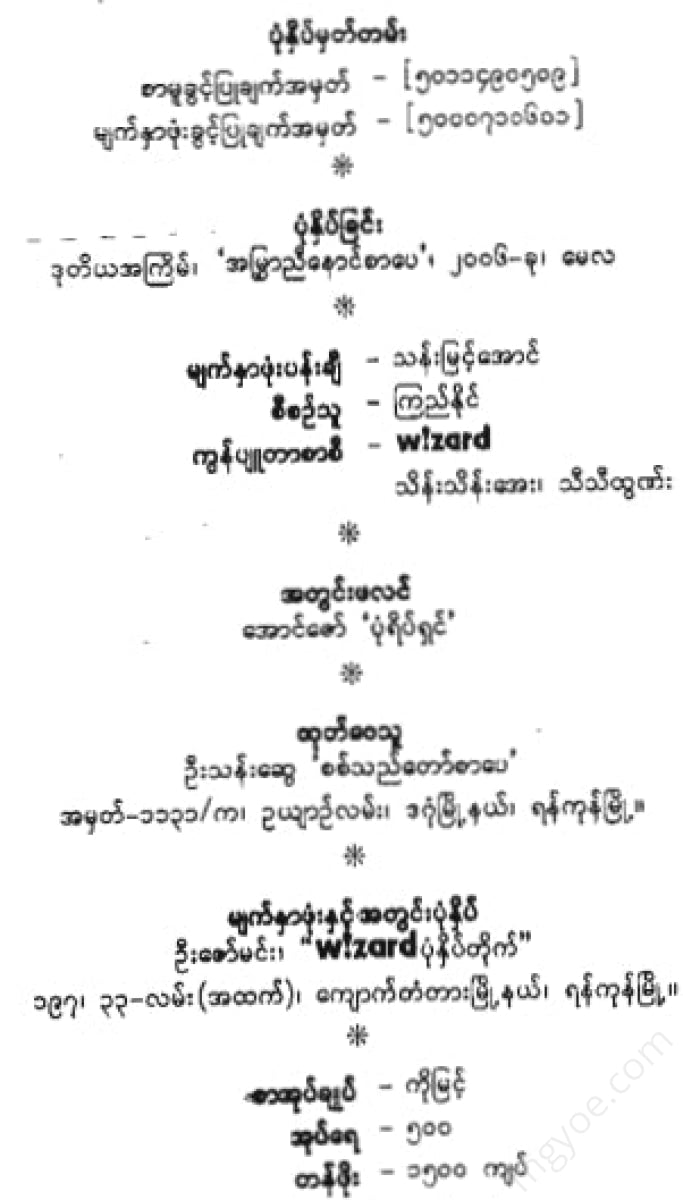

University of Nandamuri - Battle on the banks of the Salween River

University of Nandamuri - Battle on the banks of the Salween River

Couldn't load pickup availability

"I don't want you to think that helping the British troops is helping the British to return to Burma and rule. We are helping the British at this time because we want to oppose the Japanese. After the war, Burma should be ruled by the Burmese people."

Who do you think spoke the above words in front of a white-faced officer during World War II?

The person who said this was neither a political leader nor a famous person, but a simple Burmese man. The dear reader will be surprised to hear his name. He will be even more surprised to know the village where he lives. His name is Puchingui. The village where he lives is Panhai Village in Kokang District. He has no other significant honors except the title of brother of a chieftain, which the village honors him with.

However, he was a man who loved his country and people with great courage. The influence of the British troops that arrived on the eastern bank of the Salween River in 1943 and 1944 gradually increased. Even before the Second World War, he was not afraid of the British, who had become powerful and called the British Empire on which the sun never set, but with a strong spirit of independence. He said that helping the British was not helping the British to rule Burma again after the war, but was only temporarily helping and cooperating in the anti-Japanese activities. I sincerely respect and praise Pu Chin Kwe, a villager from Pan Hai in Kokang, who dared to say openly and boldly that he was helping the British again.

Like the patriotic Comrade Puchin Do of Panhai Village in Kokang, who longed for Burma's independence with a strong desire and used weapons to resist the fascist Japanese, who were few rivals in the war on the west bank of the Thanlwin River, it was the villagers of Ko Seng Village. As they vigorously fought against the Japanese, the one who particularly prevented the British from regaining control was Yang Wan Su, the military and political leader of the villagers of Ko Seng.

Ko Seng is just a poor village on the east bank of the Salween River like other villages. However, the villagers have a different mentality from the villagers in other villages. While the villagers in other villages have a mentality of avoiding the coming disaster, the villagers in Ko Seng have a strong mentality of facing the coming disaster. They have abandoned the fear of running away from the Japanese and have developed the mentality of fighting the oppressive fascist Japanese in a revolutionary way.

I would like to introduce you, dear readers, to such people with such a strong revolutionary spirit.

The villagers of Ko Saeng, instead of waiting patiently for the situation to develop, were determined to create the situation they wanted. They were also prepared with all kinds of weapons to retaliate at any time against the Japanese, who were threatening them with great force from the west bank of the Salween River. Ko Saeng was a very fertile ground for the resistance against the Japanese.

Yang Wan Wei, a political and military leader from Ko Seng village, played an important role in the history of the Burmese revolution. But... who wrote down his deeds?

Who could have written even four or five lines about the bravery of the villagers of Koesang that he led?

It has been 20 years since the Japanese Revolution, and the descendants of Ko Seng Village who are still alive today will remember the spirit of the villagers of Ko Seng, and the courage and patriotism of Yang Wanyu, who led the villagers of Ko Seng.

In this way, all the revolutionary activities of the ethnic groups born in Burma gradually faded away, with no one to record them.

I think that John Beamish, the author of the Burma Drop, which I am now translating into Burmese, inadvertently wrote about Pushin Kwe from Panhai village in Kokang, and about the villagers of Ko Seng village and the village leader Yang Wan-wei, in his opening chapter praising the British Empire on which the sun never sets. The mother of the original author, John Beamish (4), was a Burmese woman, and I wonder if John was revealing the spirit of the Burmese ethnic people who wanted to be his slaves.

In any case, I would like to express my special gratitude to the original writer, John Biermisch, for documenting the fiercely independent villagers and village leaders of the Kokang and Ko Seng regions. In other words, mushrooms grow from rotting wood. Lotuses grow from cow dung.

"When we were in trouble, the British did not come to help us, not even a single rifle. We collected all the weapons we could find in our village and defended our territory. We exchanged all the weapons we could from the Chinese soldiers for money. Well... Now that we have done all we can to protect ourselves, and our master, the British Major, has arrived, it is very sad to think about the British."

Yang Wanwei, who was in charge of the defense of the Ko Saeng, boldly said the following to John Beamish, an official sent by the British command in India.

Yang Wan Hlaing, a strong Burmese nationalist who strongly supports the idea of national independence, spoke about racial discrimination as follows.

"If you are white, you are considered civilized and educated. If you are not white, you are considered rude and uncivilized. The white-faced officials sent by the British government care more about the horses and dogs they have bred than about the people under their control."

"Those bureaucrats are only a handful. Every nation has people who discriminate like this, right? They are a minority."

I was reading intently, immersed in the debate between the original author, John Bimish, and Yang Wanwei, the political and military leader of the Ninevehs.

The image of Yang Wan Hle, the commander of the defense forces of the Nineteenth District, responding to John Beer Mish, who had arrived on a special mission to the eastern shore of the Thanlwin River, is also beautiful.

"A minority is a minority, yes, but that minority is a very scary one. The Burmese are treated as if they were not people. How can the Burmese forget this? If the Burmese like the English, if they like British rule, why are they demanding independence? The Burmese, who do not even want to live in the British Commonwealth and are demanding their own independence, have strong historical evidence to support this demand." I wholeheartedly applaud John Bimish for his response to the statements of a Ko Sein resident.

Before and during the Second World War, we Burmese people living around Yangon and Mandalay, who were generally considered to be backward, were surprisingly advanced in their ideas, visions, and political views, compared to our brothers and sisters, the Ko Seng and Kokang people, who were our blood relatives, east of the Thanlwin River in northern Shan State.