Other Websites

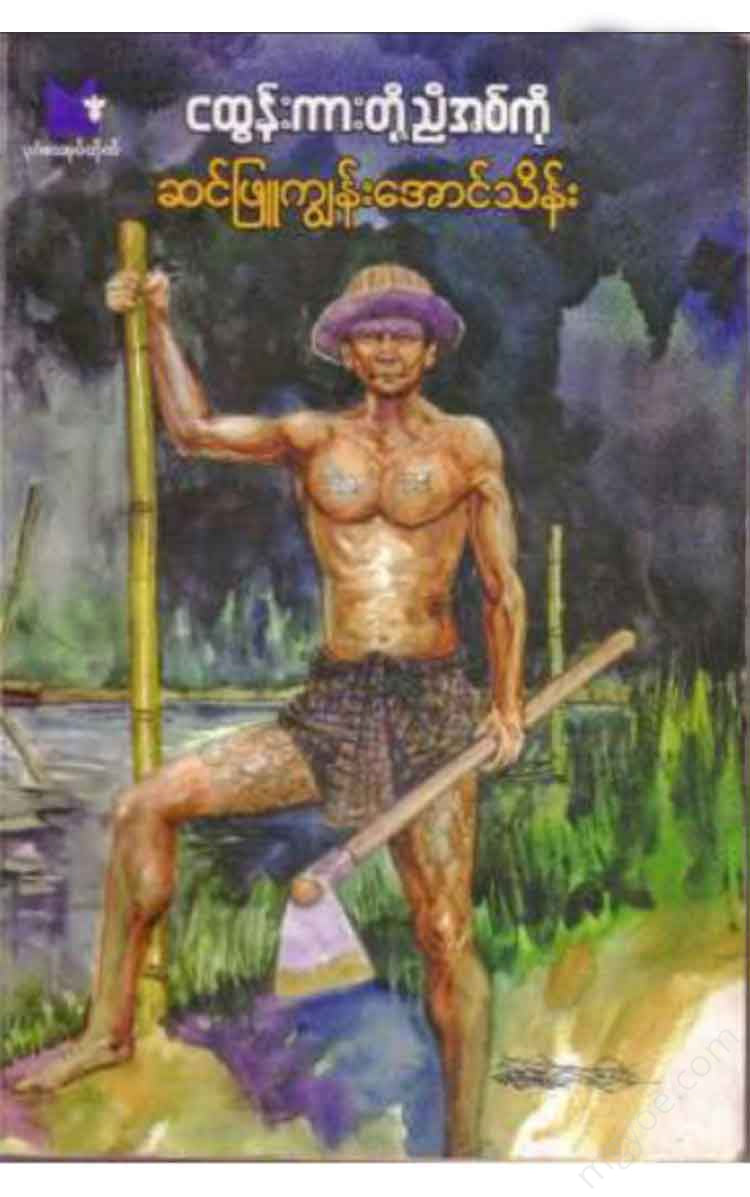

Sinphyu Kyun Aung Thein - Nga Tun Kar's brothers

Sinphyu Kyun Aung Thein - Nga Tun Kar's brothers

Couldn't load pickup availability

A grain of rice, a bean

"Hey, they're here."

No matter how blind Ri Kee Dan was, he knew from just one glance at the large group of children moving through the snow that they were his children. The children were also Abe Ri Kee Dan's. They did not go to their grandmothers, Daw Chaw Sein and Daw Hla May's houses. When it was light, they would only come to Abe Ri Sey Ro and Ri Kee Dan's house.

At the front of the long line of people, who were bent over to keep warm, were the three brothers Thura Kyaw, Thura Than, and Thura Htun. They were the sons of U Ba Nyein and Daw Hla May’s daughter, U May Kyi. Behind them, in a small group, were U Ba Thein, Daw Hla May’s second son, Ko Khin Maung Nyein, and the daughters of Ma Yee Pyone, Pyone Pyone Nyein Oo and Pyone Pyone Yee Nge. Then came U Tun Ra and Daw Chaw Sein’s grandchildren, Hi Kyi, Kata Ke and Shwe Yee Win. They called their mother, the great-grandmother, Ree Kyi Dan, Kyi Phyu or Ma Kyi Phyu, and the rivers were sitting around the fire.

"Roll, roll, sit down."

Ree Se-roe ' made the palm leaves into cushions and made them into seats.'

"Take the cloth and don't let it fall into the dust," he said.

They sat down, their eyes fixed on the bottom of the stove. The stove was surrounded by palm roots. The palm roots were not placed in the fire or on the coals. They were placed between the hot earth and the hot stove.

"Don't just stare. Mom and Dad haven't eaten yet."

The one who made Ri Qi Dan's eight-fold face smooth and clear, having passed his family and ancestors to the ancestors, was brave.

There were no dirty brown and black palm roots scattered around the stove. There were no white cores or fibers, so it was clear that no one had eaten palm roots that morning.

There was no pot of rice beside the pot. The pot of rice was still under the tamarind tree behind the pot. The pot, which was placed on the stove with a sand base (like a stool), was just beginning to emit steam from its spout.

Seeing this, Kata Ke became a teacher to his brothers and sisters. Ree Se Yo smiled.

"You're a very good boy. You made me want to feed you what your mother didn't want to feed you, didn't you?"

"Courage is the key to success"

The person who spoke was my cousin, Aung Kyaw San Oo. Although he was small in stature, his voice was powerful.

"I got the machine, bro."

The grandmother suddenly emerged from the snow-covered ground at the foot of the house. The one who ran and talked was Maung Ko Gyi. He looked like a cold person with a wide shirt and a short beard. He rushed in among the nephews and nieces. He pressed close to the stove.

He is the eldest son of the eldest daughter, Ma Chaw Sein. He works in the backyard of his mother's house and works on his mother's farm.

"I want to die in such a cold place with a big blanket."

Despite the scolding, Maung Ko Gyi did not lose his face. He pulled out three palm roots that were tied in a row. The skins of the palm roots were not blackened. The original color was not lost. However, they were brittle. Maung Ko Gyi scratched the palm roots with a small knife, and the palm roots appeared white. After scratching two of them, he gave one to his father and mother, and then peeled one for himself.

"Grandpa only knows about himself"

A faint voice came out, and Maung Ko Gyi remembered his nephews and nieces.

"Heh heh heh sorry sorry"

As he pulled out five more palm branches, Ri Qi Dan asked his grandson, dodging the smoke that was coming towards him.

“You just said that. What kind of machine?” “A harvester, mother.” “Are you renting a machine because you can’t handle the ropes, man?”

"I don't rent a combine because I have a machine, Mom. If I can rent a combine, I have to wait until the rice is ripe. When I rent a combine, it comes with a threshing machine as well."

Maung Ko Gyi answered his mother's question. He peeled five palm roots. After peeling the palm roots, he divided them into halves and distributed them among his nephews and nieces, leaving only one left.

"I'm doing good deeds with the Ngachibong," came a voice from the darkness in front of the house.

"Step forward," Maung Ko Gyi had already reached the source of the sound as the shouts continued.

"Sadhu, Sadhu, Sadhu. The sound of the

It is a custom in this area to not only donate the rice bran to the monasteries, but also to distribute it from one village to another. Some people also give away rice bran cakes, which are made from rice bran. Maung Ko Gyi took the rice bran wrapped in banana leaves and ran to the stove. It was about half a cup. .

"Well, are you running out of fuel?"

While Ri Qi Dan was still grumbling, Maung Ko Gyi ran upstairs. He brought down a jar of oil and a salt shaker, as well as an iron bowl and plates.

Maung Ko Gyi poured the sticky rice noodles from his plate into a bowl and handed it to Ri Kyi Dan.

"My mother won't be able to eat it, son. You just fry it, sprinkle it with salt, and distribute it to your relatives."

"I can't stand the smell of the skunk, mother." "I can't stand it, I can't stand it."

Maung Ko Gyi sprinkled salt on the sticky rice. Knowing May Gyi's mouth, he didn't use the oil burner. He handed the pot to May Gyi.

The old woman threw the hidden nut with a single blow from a bone-studded stick.

For rivers, the riverside of the palm tree is not fragrant. When the smell of the incense wafts, people are already standing with their mouths open.

Maung Ko Gyi bowed down to give a bowl to his mother and father. He gave each one a bowl. He also gave a bowl to the children.

"Are there many beans?"

The father said with satisfaction as he chewed his gum. The mother looked at the rivers that were swallowing the food in a hurry. "Eat carefully. If you drop a grain, you will have to pick it up one day," she said sternly.

Maung Ko Gyi carefully placed the oil pot and salt at the base of the tamarind tree, then placed the bowl of sticky rice in the basket. He turned around and said as he scooped up a handful of sticky rice.

"It's not good to ask someone to pick up food that has already fallen on the ground, on the mat, on the floor, and eat it, mother. It's not clean at all."

Then, Ree Se-roe placed the bowl of sticky rice soup on the small stool and picked up the bowl of hot water. “This is what a man should do,” he said.

While Maung Ko Gyi looked up, Ree Syeo was still getting some hot water.

“I want you to respect the rice that represents you as the master of life. And it is not as easy as it is today to turn a sesame seed, a bean, or a grain of rice into a grain of rice. In your time, we had to build dams, canals, and fields. In the time of our fathers, there was not even a Lin Zin canal. The only thing that was a canal was a small stream with a small stream.”

"A house, a bag of rice, a knife, a torch, a plow (plough), and a pair of oxen. We have to go to the dam at midnight tonight."

The farmers of Tha Dunwa Myaung Myaw have been listening to the sound of the Myaung Head for three days. It was since the Myaung water had stopped. The farmers who had built a dam in a rice field were cooking. They understood that the dam had been damaged a lot because it would take a long time to finish a rice field.

The torch is for lighting at night. The torch, also known as the flashlight, has not yet reached the countryside. The plowshare is a tool made of palm leaves that are woven into the plowshares. It is used to dig a ditch to remove sand that has been carried into the ditch.

The poor man's canal is a self-reliant canal. It was not built to be inspected and maintained by the king himself. Therefore, there is no 'Bin Thar' to guard the dam and the canal. Only the canal heads take turns supervising. The dam, which faces the right and is built on a sand bank, has three dam pillars, one cubit apart. It is also called a 'Tiktok Si' (tree branch dam) because tree branches are placed between the dam pillars .

The stream was flowing slowly. It flowed smoothly into the canal, which was dammed with a wooden branch. The farmers were plowing and planting with a loud voice. The stream was flowing furiously, tearing down the banks and carrying away the trees. The dams were clogged with weeds. The sandbanks and the dam pillars were swept away by the water, and the sound of the nursery was drowned.

"We have to climb the dam, huh?"

The wooden dam is extremely unstable.

The people who climbed the dam returned home, but their backs were still warm. Myaung Kaung came and said in a voice of anguish, “Brothers, if there is no rice, add a cup of rice and get ready to climb the dam, brothers.”

At that time, Kyung Gyi and Ma Kywe Soe became farmers in Tha Dun Wa. They started by experimenting on ownerless plots of land. The year they tried it, the water was right. The weather was good. As a result, they earned about ten baskets of rice.

The price of rice is three marks per head or one kyat, and the rich and the poor do not know. Since they are almost self-sufficient, they think the taste of farming is sweet.

Ko Kyaw Gyi and Ma Kyaw Soe have grown greedy. It doesn't matter if they don't. Despite working and eating at random, they have three children. The eldest is Nga Thun Ka, the middle one is Si Ro, and the youngest is Mae Myint.

While searching for new land, Ko Zang Gyi and Ma Kywe Soe found a new land at the edge of Tha Dun Wa Myaung. The forest was covered with a large yam tree, two kukkos, and a ka tree. Ma Kywe Soe carried her son and worked as a coolie, while Ko Zang Gyi used a machete to cut the forest. Since she had left her two sons at the monastery, she did not have to worry about them crying when they were hungry. However, Ko Zang Gyi could not work alone in clearing the land. Although the two sons were young and weak, they could control the "snake" side. They could cut branches and branches. They could boil water, find firewood, and find food. Therefore, Ko Zang Gyi had to go to the monk without any fear.

“My disciple is living in a forest near the edge of the Thar Dun Valley. Please call the children to make a taukto.”

The monk does not scold. He knows what his disciples are saying.