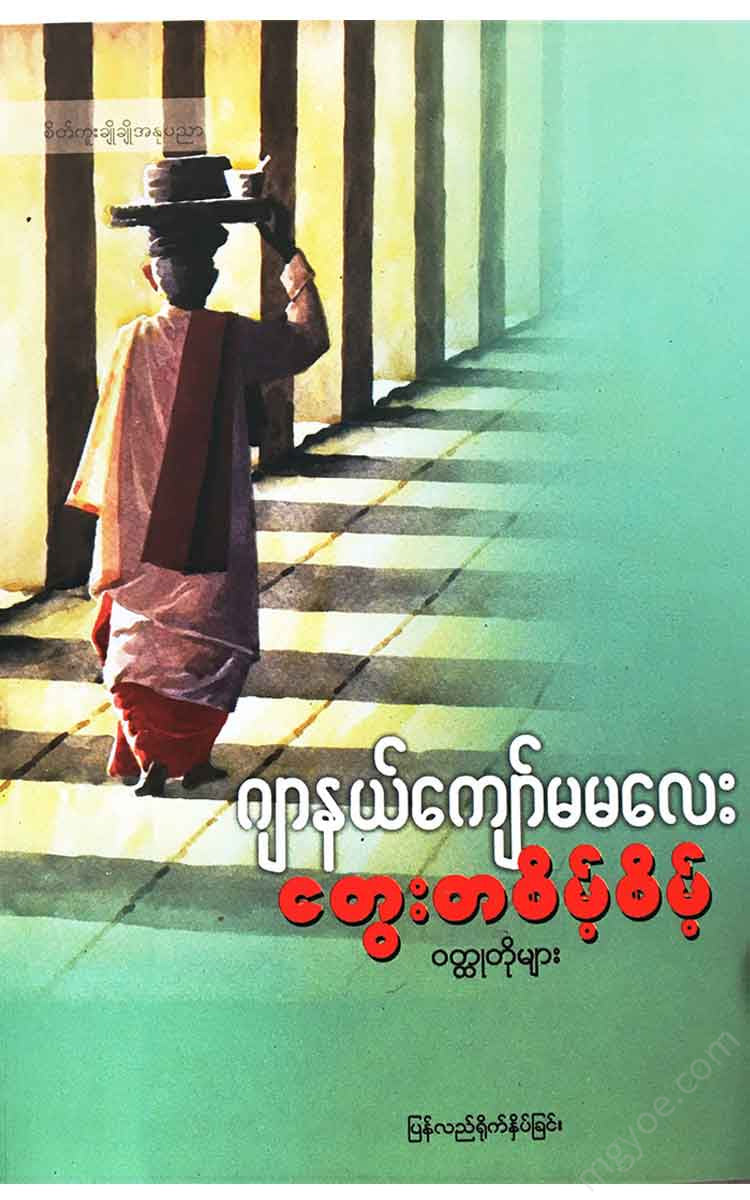

စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

Journalist Mamalay - Thinking of You

Journalist Mamalay - Thinking of You

Couldn't load pickup availability

Author's note

In the post-war period, in 1948, I published my first collection of short stories under the title Shumangi, which was a collection of short stories I had written. The stories included in Shumangi are Aye Aye, Mi Kwo, Bahira, Nye Myo Myo Day, Dhamma Polik Kwet, Meen Pi Pi, Ee Saung, Ma Ma Ma, Ee Moe.

This is the second collection of short stories written after the publication of Shu Ma Kyi in the collection of short stories "Thinking and Thinking" and is being published collectively. There are plans to publish the remaining short stories for the third time.

The short stories in "Thinking About It," "A Little Grass," "A Beautiful Face," "The End of the Cycle," "Khemari," "Thinking About It," "A Purchase and Its Pleasure," "The Heat," "The Power of the Power," and "Kafie" are usually about emotions and feelings that arise when we see, hear, or know something. These emotions arise when we experience something, whether it is a happy feeling or a sad feeling, a feeling of joy, sadness, liking, disliking, compassion, or disgust. These are feelings that arise from gaining some kind of knowledge of life.

They are short stories.

When I wrote these short stories, I tried very hard to turn the subjective into the objective. I wrote with mindfulness and restraint as I described the perception of life, human nature, and the mind of life.

If we become aware of the interests of others, the events of others, and the affairs of others, only then can we become aware of our own interests, events, and affairs. Therefore, we wrote these short stories with the intention of inspiring readers to read them and to use their innate intelligence to penetrate and reflect on human nature and the nature of the world, and to be aware of it. We wrote them with love.

Journalist Ma'am

27-9-63

Thoughtfully

Daw Thein Mi sighed.

He felt a little relieved inside, but he sighed deeply inside. He had to rest his hands and feet, which were so stiff that they were unable to move.

Daw Thein Mi sat cross-legged on the deck chair, eating and looking tired every night.

"Today is the most tiring day," he remarked, sighing inwardly.

There was no water in the house. In the afternoon, I had to fill two large iron drums with water from the pump on the corner of the street, which was tiring. I filled them with water and sat down to wash a large pile of old clothes. I counted the clothes on the line and found that there were seventy-five of them, and I was very tired.

Daw Thein Mi's head was rolling back and forth on the armchair. She was gasping for breath and moaning endlessly in her mind.

At this age, do you still have troubles as big as mine?

Daw Thein Mi is 61 years old. Her only problem is that she has to do housework all day long, from sunrise to sunset, without any earplugs. | She gets up at 4 am and goes to the kitchen. After lighting the kettle, she quickly cleans the fresh and new things. While Apu, Htut Ni and Putu Ma wash the milk bottles that they have been drinking from the night before, Ko Shwe Nyaung returns home after midnight and continues to wash and clean the rice dishes and dishes that they have eaten for dinner, while she keeps the kettle on and the rice bowls clean. She makes coffee for the whole house. She holds a coffee cup with her left hand and drinks it, and crushes chili with her right hand.

While the rice pot was still on the stove, she crushed a handful of chili peppers, prepared the food tray, and filled the bottles of milk for the children to drink when they woke up. Then, she put down the rice pot and, calling from the door of the room where her daughter was sleeping, ran to the morning market.

Since I had to drop off my three children, Ama and Apu, who were going to school at 8am, I had to rush home from the market to cook and feed them. I took the two youngest children, Ama and Apu, by the hand and ran them to school before my son-in-law went to work.

Daw Thein Mi's son-in-law, Maung Mya Oo, is an office clerk. He arrives at the office at exactly nine o'clock. Daw Thein Mi's daughter, Ma Aye Hla, has been married for a long time, but she has not been in good health, and she has only given birth to one child a year, and she lives on gold and silver every day. She is four months pregnant and her legs are swollen, and she has been bedridden for about a month.

In the morning, I was busy with household chores on one side, babysitting on the other, student affairs, office work, taking care of my sick daughter, and so on. At 11 o'clock, I had to run to school to pick up my children. Not having water in my house was even more of a problem. I had to carry water from the fire hose on the corner of the street with a hand-pulled iron bucket all day long. I had to wash my daughter's clothes, my son-in-law's clothes, my children's dirty clothes, and all the old clothes that were left.

While doing laundry, I had to do various other tasks on the side.

The baby bottle, the swing, the baby's back seat, and the way he often goes to the toilet are all done with a wet towel from the laundry.

There was no helper at home, so I was busy doing various chores while washing clothes and reading. After washing clothes, I took a hot bath, went to bed, and went back to the kitchen for dinner.

While the rice was cooking, she was busy sweeping the front of the house. She had to bathe the children one by one and apply Thanaka blood. She had to make milk bottles at the same time every hour. She had to swing the baby's cradle. The rice pot was boiling, so she ran back to the stove and continued to work. The tasks she was doing were not one after another, but a series of tasks, all of which she did in a hurry, not stopping until the sun went down.

Daw Thein Mi could only sit on the deck chair at 10 pm. From sunrise to sunset until 10 pm, she had to do one thing after another, moving around and doing it all. When all six of the little ones were asleep, she sat down on the deck chair, unable to move her legs or arms, exhausted. Both arms were really sore. Her back hurt. Her knees hurt. She had been working non-stop all day, and it was tiring, but she had to shout, talk, and pull the little ones who were playing until they lost.

Daw Thein Mi, who had been carrying a load of people and noise all day, would become weak when she reached the chair at night. She was so exhausted and barely breathing, she heard Ma Aye Hla moaning in her bedroom, biting her thigh.

"Do you have a hot water bottle?" he said, his voice straining and straining to be heard.

Ma Aye Hla, who was moaning, heard her mother's voice, so she stopped moaning and gritted her teeth, listening intently. Daw Thein Mi's voice was hoarse, as if she had just reached the top of a mountain, her voice breaking and trembling, her voice breaking.

Ma Aye Hla stopped crying. “Yes... I did, Mom,” she cried out. Then she buried her face and head in a pillow and cried silently, falling to the ground.

Daw Thein Mi woke up to the sound of mosquitoes buzzing around the edge of her deck chair. She was so scared that she couldn't lift her arms, when a mosquito came and bit her, she was so angry that she couldn't hold it in her mouth. Her face, which had only five teeth, was so swollen that it looked like a sack of red cloth had been tied up from top to bottom, and her eyes, nose, and mouth all wrinkled and shrunk.