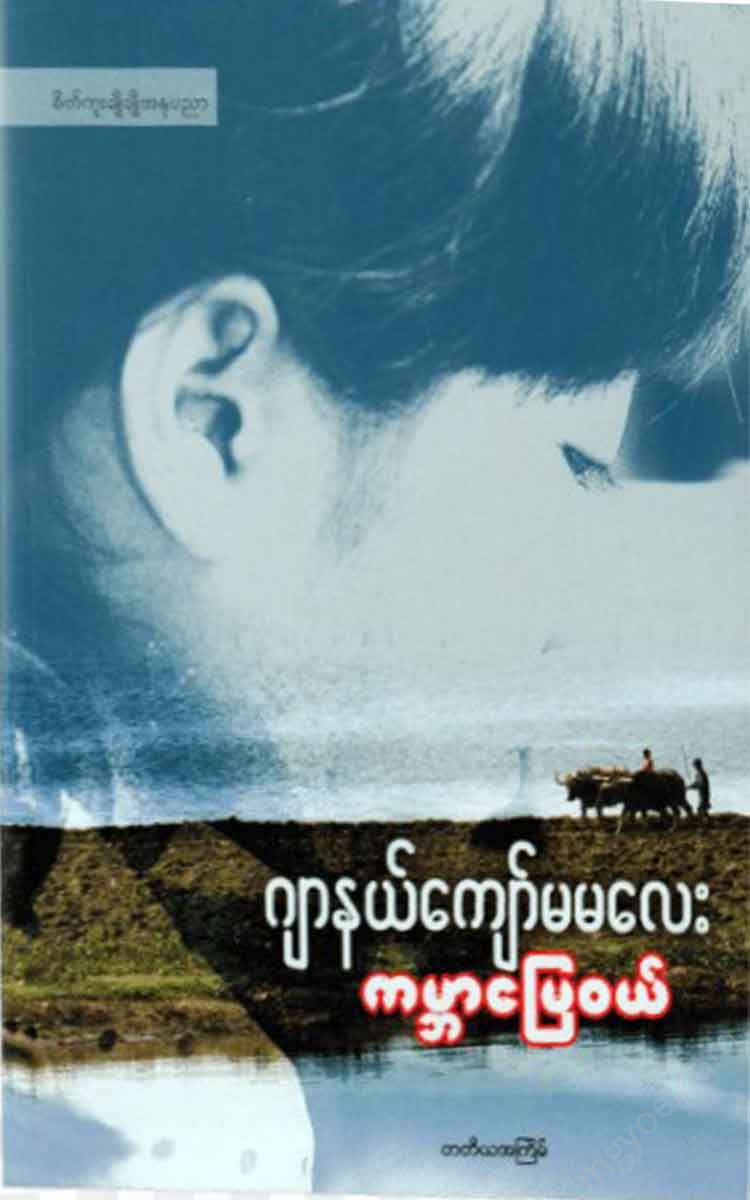

စိတ်ကူးချိုချိုစာပေ

Journalist Mamalay - Buy the Earth

Journalist Mamalay - Buy the Earth

Couldn't load pickup availability

He didn't sit still at the back of the cart, but started to move his legs.

"The dog is going to fall," U Thu Taw said, turning around.

The sun was shining brightly, and the evening was unusually pleasant, unlike the summer and winter evenings. The cart road from the village of Kyaukta to Kamakalay was paved through the fields. The road was dusty. The fields were dug up and the ground was leveled to a height of about a palm's length.

On both sides of the road, there were only fields, one above the other. The water in the fields was overflowing and white. The grasses that were sprouting from the water were green in the warm sun.

As I sat in the back of the cart, I could see the village of Ohn Nee, covered in large white flowers and hibiscus trees, from a distance along the road. It was adjacent to Ohn Nee Village.

The iron gate, the Nirvana, and the village children were also standing in awe. On the other side, if you look up over the fields, you can see the Bago River. The tall, sturdy boats are floating in the river. On the other side of the river, there is a railway track.

The cart's wheels clanked and clanked as the oxen pushed in front of the cart. U Thu Taw was still awake, slowly driving the cart. The sun was shining brightly, reflecting the green landscape.

Hla Nwe looked up at the mountains beyond the villages. The common mountain trees, the sedges, the bamboos, the sedges, and the bamboos were lush and green. At the foot of the hills, the farmers' huts were clustered together, huddled together. As she gazed at the surroundings, she felt calm and even forgot the smell of manure.

At the turn of the field, I heard the farmer shouting to the cows, “Hey, let’s go!” and I turned around. The farmer was wearing a long-sleeved shirt, a helmet, and a short skirt, and was plowing. He had five wooden tines attached to the plowshares and was forcing two cows to pull. When the cows pulled, the clods of earth would rise from under the tines, and the trees would grow. The Hla Nwe was plowing.

He looked at the unripe rice plants one by one, looking at them with his hand. -

U Thu Taw also said to Hla Nwe, who was sitting quietly behind the cart, "Girl, have you seen your father yet?"

"I've been there."

In Hlanwe's eyes, I see green, vigorous rice plants.

Looking up, the rice plants swayed in the wind. He spoke again, happily thinking that they were the rice plants he had planted. Then, the little birds were tearing the rice stalks and he was happily running around the field with a stick.

``Yes---, increase, try to hit, gold and red, what a gamble

U Thu Daw's two cows, who had been carrying and carrying cow dung all day long, were getting tired. If their growth was slow, Shwe Ni would follow. Even after he beat each one on the back with a whip, Shwe Ni would know that if he was hit, he would fight back with great force.

Hla Nwe was running in the field with a stick, when she heard a voice from somewhere, and her thoughts stopped. "Don't hit me, U Thu Taw. They are also afraid."

He looked up at the cows, feeling sorry for them, as he stepped over the pile of cow dung that had been piled up behind him.

“Whose cart did you take when you went?” “We went with the charcoal cart, Ko Kyaw Ni.” “Are you going to your father's?”

"I didn't go to my father's house on purpose. I went to pick up the rice-planting shirt that Daw Thayar had left at the machine when I got in the car."

U Thu Taw looked back and saw the rice plants swaying in the wind. He was happy and satisfied with the thought that they were the rice plants he had planted. Then he spoke again, happily, while the little birds were tearing the rice stalks and he was running around the field with a stick, driving them away.

``Yes---, increase, try to hit, gold and red, what a gamble

U Thu Daw's two cows, who had been carrying and carrying cow dung all day long, were getting tired. If their growth was slow, Shwe Ni would follow. Even after he beat each one on the back with a whip, Shwe Ni would know that if he was hit, he would fight back with great force.

Hla Nwe was running in the field with a stick, when she heard a voice from somewhere, and her thoughts stopped. "Don't hit me, U Thu Taw. They are also afraid."

He looked up at the cows, feeling sorry for them, as he stepped over the pile of cow dung that had been piled up behind him.

“Whose cart did you take when you went?” “We went with the charcoal cart, Ko Kyaw Ni.” “Are you going to your father's?”

"I didn't go to my father's house on purpose. I went to pick up the rice-planting shirt that Daw Thayar had left at the machine when I got in the car."

U Thu Taw looked back and saw the rice plants swaying in the wind. He was happy and satisfied with the thought that they were the rice plants he had planted. Then he spoke again, happily, while the little birds were tearing the rice stalks and he was running around the field with a stick, driving them away.

``Yes---, increase, try to hit, gold and red, what a gamble

U Thu Daw's two cows, who had been carrying and carrying cow dung all day long, were getting tired. If their growth was slow, Shwe Ni would follow. Even after he beat each one on the back with a whip, Shwe Ni would know that if he was hit, he would fight back with great force.

Hla Nwe was running in the field with a stick, when she heard a voice from somewhere, and her thoughts stopped. "Don't hit me, U Thu Taw. They are also afraid."

He looked up at the cows, feeling sorry for them, as he stepped over the pile of cow dung that had been piled up behind him.

“Whose cart did you take when you went?” “We went with the charcoal cart, Ko Kyaw Ni.” “Are you going to your father's?”

"I didn't go to my father's house on purpose. I went to pick up the clothes that Daw Thayar and his wife had left at the machine," Hla Nwe said, her lips pursed, her two dangling legs twisted and swayed back and forth.

"You know how to plant rice..."

“Ah... U Thu Taw said, you have to plant and grow. If you plant temporarily, you only get one seed per pot. When you learn to plant, you can grow it for a living.”

“Do you know what a dog breed is?” | Hla Nwe turned her head and glanced at U Thu Daw. U Thu Daw pushed Hla Nwe back and continued to drive the cart. Hla Nwe turned her back on U Thu Daw. .

“When picking seedlings, I held them four times with my hands and tied them together. That’s what I call a bundle.”

"'Oh, the monk's daughter is a big girl, heh heh."

Hla Nwe heard the old man's toothless laughter. She was also irritated when the monk's daughter called her. She picked up a piece of cow dung from the dung heap and sat down in the bushes in the field.

He threw the body away with all his might. He watched the little birds flying away in fear and panic, with all his eyes.

“Where should I plant it?” “In the rich man’s field.” “So you won’t sell boiled beans anymore.” “My mother will sell them.”

Hla Nwe suddenly remembered Mya Tin. She was also shocked inside.

Mya Tin's hut has a debt of boiled beans. If my mother knows, she will tell me. My mother told me not to sell the debt. Mya Tin still has a fever, so she gives me a cup of boiled beans every morning to eat. She said she will pay the money later.

"I was forced to sell my clothes at the market, I was in debt, I was asked to work, I sold my things here and there, I was so angry that I was beaten by my father, I can't even say it, I just want to die."

Hla Nwe, while her mother was angry, kept her head down and kept quiet, blaming herself. If she had paid the debt, the smoke would never end, the rain would never end, and she would have been scolded and beaten.

"Next time I hear you giving me a loan, I'll fix it so I can die. Don't try to sell me a loan, you hear me?"

Hla Nwe trembled and left. It's impossible. It would be difficult to repay the debt to my mother while she was planting rice in the morning. - U Thu Taw, I won't go to Kamala, I'll go down to the machine shop. Stop, stop."

"What is this girl doing in the machine?" U Thu Taw pulled the rope and slowed the cart. Chai quickly grabbed her shirt and jumped off the cart. She twisted her neck to see if there was any cow dung on her shirt, and patted her buttocks with her palm. Chai grabbed her shirt and shouted, "Because I have a debt to pay."

He got off the cart path, crossed the Kanthin wall, and walked for a while, then said, “Hello,” and looked back at the cart. The cart had already reached a short distance. He stood there, his mind hesitating, then he galloped behind the cart and ran.

"U Thu Daw... U Thu Daw," he heard a voice calling from behind. U Thu Daw turned around and pulled the rope. "I'm not going to the machine anymore, I'll just follow."

As they spoke, they climbed onto the cart and sat down next to it. “Yes.... This girl,” Hla Nwe giggled. “What are you laughing at, you idiot?” U Thu Taw asked. “You know how to laugh, U Thu Taw.”

"If you tell me that I was left in debt at the factory because I met U Thu Daw and my mother, I still remember the trouble," Hla Nwe thought to herself and burst into laughter.