Other Websites

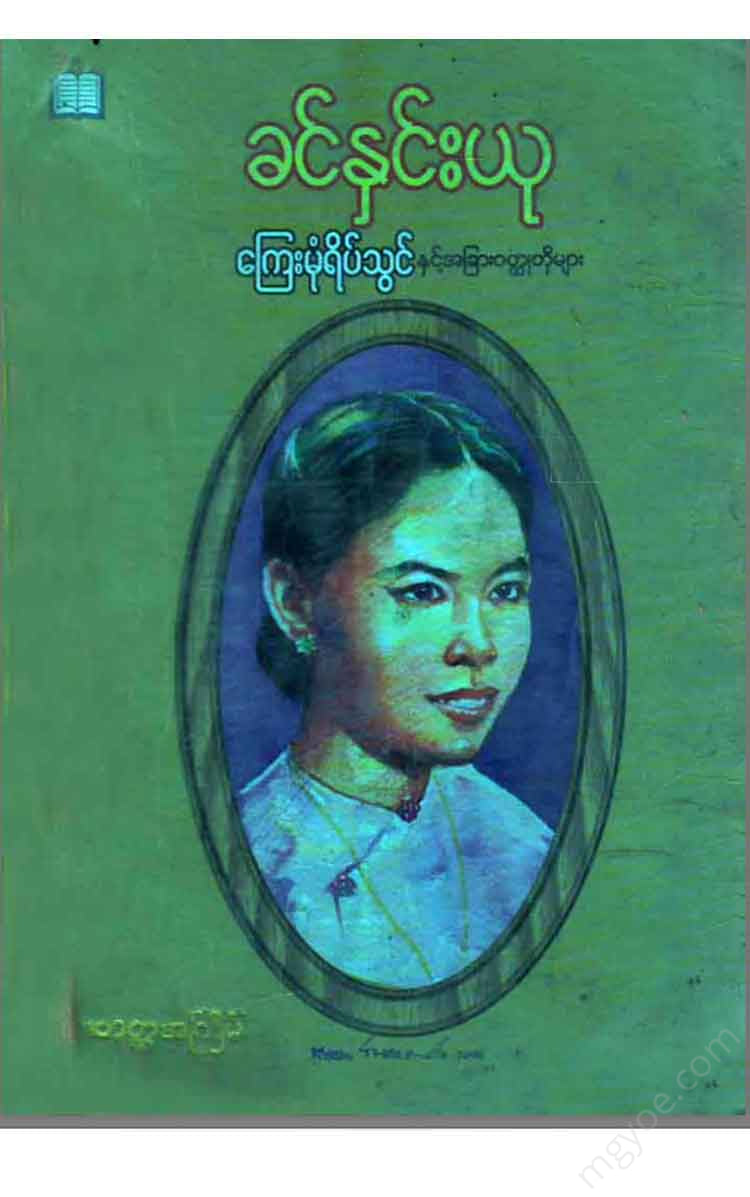

Khin Hnin Yu - The Mirror's Reflection and Other Short Stories

Khin Hnin Yu - The Mirror's Reflection and Other Short Stories

Couldn't load pickup availability

Introduction

The short story, which is called "Kalapaw", is new to Burmese people. However, we Burmese have been telling stories that contain a sense of humor since our origins as a nation. Fathers, mothers, grandfathers, and grandmothers have been telling stories that began long ago to their children and grandchildren until now. From the Golden Rabbit and the Golden Tiger mowing the thatch to the Mabeda water-draining river, the treasure trove of stories filled with lovable characters and interesting events can be said to be a treasure trove of our own people.

Although it can be said that the Burmese have their own treasury of stories, it does not mean that they are only stories invented by the Burmese themselves. Cultural matters do not stand in one place. As long as there has been interaction between the peoples of the world even before the advent of modern times, cultural objects, ideas, and sciences have also spread. Especially, it is difficult for any nation to put its own stamp on everything that has been created and created by the human mind, no matter who first conceived it. If you look at the spread of the major religions believed by many people in the world, you will know that this is true. If you look back at the history of cultural objects, you will find it in the same way. Paper and gunpowder first appeared in ancient China. They gradually spread to the western regions and were able to be produced by the industrialized western countries, so paper and gunpowder returned to modern China in a new form. “The smoothness of paper and the great power of gunpowder were new to the Chinese. Astronomy and mathematics returned from the East to the West. They returned to the East in new forms due to various improvements and inventions. The Easterners were taught by the Westerners as disciples and learned the profound sciences. The numerals we use in Myanmar, from 1, 2, 3, to 10, were originally the same as the English numerals from 1, 2, 3 to 10. This numeral system also spread from India to eastern Burma. It also spread to the West through the Arabs. When the English adopted it, it became the English numeral system. When the Westerners came to dominate the world, the Easterners thought it was delicious to write 1, 2, 3.

India and China were not only the birthplaces of civilization and science, but also the centers of creation and invention of stories. Indian stories spread both east and west. For example, there are ancient Hindu stories like Shin Mu Nun and Min Nanda. They spread west and emerged in Greek literature as the story of Hero and Leander. Fairy tales also traveled east and west from India. They are included in the ancient stories of Myanmar. They were written in English and printed in Myanmar and returned to Myanmar as the fairy tales of Esup.

Short stories are new to Myanmar - they are read and written as a genre, but the short story has been ingrained in the blood of the Burmese since ancient times. Although they are not called short stories or recognized as such, the Burmese have been reading, remembering, and liking literature that contains short stories since the arrival of Buddhism and the introduction of written language. The Five Hundred and Fifty Nipas can be called short stories from a literary perspective, not from a religious perspective. I do not want to think that I am belittling the Five Hundred and Fifty Nipas by calling them short stories. I do not want to imply that the Five Hundred and Fifty Nipas are not Buddhist sermons but purely imaginary stories by calling them short stories. Although they are sermons, if you look at the form and content, you will see the appearance of a short story. In the minds of the Burmese, whether they are short or long, they are often considered to be a composition of love stories that are often found in the stories of the beloved. They tend to think that only secular literature that stimulates sensual pleasures should be called novels. They want to prohibit the term "vutthu" (literature) from being called "dharma". The novels of Sale U Punya prove that this idea is incorrect. U Punya's novels such as the novel "Saddansinmin" and the novel "Kakaviliya" are short novels that are intended to teach religious lessons, but they are short novels in nature. In the history of Burmese literature, apart from these five hundred and fifty Jatakas and the novels of U Punya, there are few works that can be called "vutthu" (literature). The five hundred and fifty phatthu are from the Bagan period, It appeared in the Inva period and in the Pepurapaiks. It was written in a mixture of Pali and Burmese. U Punya appeared after the Konbaung period. Among these periods, the only known short story that can be found, as far as I know, is the Zinmae Pannatha, which appeared in the Taungoo period. The Zinmae Yakkatha came to Myanmar from the Zinmae side, but it was originally a Dwiyadana scripture written in Sanskrit from the Tibetan side. This short story, which can be called a summary of short stories, is an example of the spread of literature from one country to another and from one language to another. In addition to the literature I have just mentioned, there are probably other works in the history of Burmese literature up to the English period that can be called short stories. For example, the novel by Karma Dik Mingyi can be called a summary of short stories. As I am not familiar with Burmese literature, this is all I know. Khon Taw Maung Kyabham Short stories such as Kuttho can also be called short stories. However, overall, Burmese literature is mostly found in the form of poems, poems, prose, plays, histories, and sermons. At the end of the Konbaung period and the beginning of the Aung San period, six-pyait plays were very popular, and in a way, they can be called the forerunners of short stories.

During the English period, English readers read English short stories. They translated them directly and adapted them. Among the short stories translated into English, Dagon U Ba Tin's father's Pathi Tales was probably the first. It was published in 1910. Then, from the 1920s, magazines such as Thuriya Magazine, Dagon Magazine, and Tain Zaw Newspaper appeared, providing opportunities for those who wanted to write short stories. The pen names of Pee Moe Ning, Shwe U Daung, Nyarna, Zeya Sattar, and Dagon Shwe Maw were short story writers who emerged during that period. They can be said to be great pioneers in Burmese short story writing. After them, great writers such as Maha Swe, Zawana, Thukha, Thakha, and Dagon Khin Khin Lay also emerged and made the short story more popular with the Burmese people. The short stories written by these great writers, starting from Pee Moe Ning, also included their own inventions. English short stories are also adapted to suit Burmese tastes. It would be wrong to say that English short stories have been adapted here. Translation is the process of translating the original text into another language, either completely or with a few exceptions. The novelists mentioned above have either translated or taken the plot of the English short story and created it with Burmese names, characters, and Burmese surroundings and mannerisms. It would be more accurate to say that they have written English short stories.

From the 1930s until the war, modernist literature emerged, with the likes of Sain Maung Wa, Uthman Maung Thant, Zaw Gyi, Min Thu Wan, Thein Nay Nwe (U Thein Pe Myint), and Sain Soe Hla becoming famous, and this marked a new era in Burmese short story writing. It can be said that a new chapter was opened. In addition to the increasing number of people writing with their own ideas, rather than relying on English novels, short stories were written with the aim of entertaining the reader and refreshing the mind, and were written with a clear sense of literature, and with a precise and neat ratio of beginning, middle, and end.